The Mediator

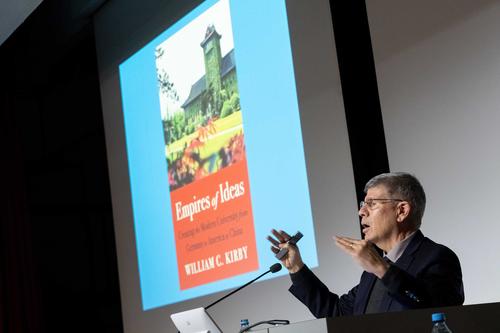

China expert and historian Prof. Dr. William C. Kirby spoke at Freie Universität about Chinese-American relations and the history of the modern research university.

Feb 23, 2023

Harvard professor Dr. William C. Kirby is a leading China expert, renowned historian, and honorary doctor of Freie Universität.

Image Credit: Michael Fahrig

If you ask Prof. Dr. William C. Kirby which job title most closely fits him, whether he sees himself as a sinologist, a China expert, or a university lecturer, he answers, "as a historian."

Kirby says this even though he is considered a leading China expert in the United States. He can talk about the reasons for this as stimulatingly as about any other subject on which he is asked. Kirby does not want to be an advocate for either side, but calls himself a "translator," a mediator. The way he carries out this task also distinguishes him in a very special way.

But back to his self-description as a historian: Kirby is currently "T. M. Chang Professor of China Studies" at Harvard University and "Spangler Family Professor of Business Administration" at Harvard Business School. He has taught at Harvard since 1992 and has held various university posts, including chairman of the Institute of History, director of the Harvard University Asia Center, and - from 2002 to 2006 - dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences.

Even when Kirby produces so-called "case studies" for the Harvard Business School, as he has recently done with great interest, i.e., case studies on individual Chinese companies and their development, strategies and potential, he is particularly interested in what can be learned about Chinese society. And he insists that this is not possible without knowing China's history, which, by the way, did not begin in 1949 with the People's Republic, but long before.

The subtle irony of his texts

Kirby is a historian through and through, exploring the past with a curiosity that is not merely academic. To explore "how it actually was" is, after all, also to understand how our present came to be. This takes away the "naturalness" of everything that is today, creates distance, and makes what is today appear in a new light. Kirby is not a historian of necessity, but entirely on the side of contingency: Yes, the task of the historian is to search in the archives for why things came about the way they did. But this search for clues always leads to the realization that things could very well have turned out differently. From this insight stems the subtle irony with which Kirby writes his texts and with which he narrates.

"History is never inevitable," says Kirby. What he means by that is also evident in how he responds to the question of how, in fact, his interest in China developed. How did he become a China expert, a China scholar? Kirby's answer is not a straightforward path, but a development full of surprising twists and turns. The personal and the general are intermingled, coincidences combine with necessary consequences of earlier events, causality and contingency become intermingled.

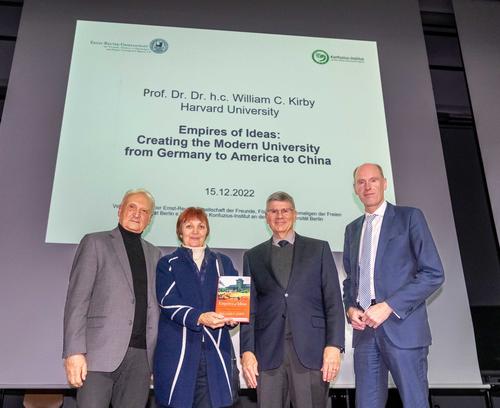

At the invitation of the Ernst Reuter Society, William C. Kirby presented his new book "Empires of Ideas: Creating the Modern University from Germany to America to China".

Image Credit: Michael Fahrig

Kirby says that he first became interested in German history in high school, partly because of his German and French teachers, and partly because of his neighbor across the street, Isabel Hull. Hull, by the way, would later become a leading historian of German history in the U.S., including as chair of the History Department at Cornell University. So it is with her that Kirby shares an interest in history, which leads him to Dartmouth University as an undergraduate. As early as his second year, he also spends time in Mainz. Soon, however, a course at Dartmouth got him interested in the history of China, simply because it was a "first-class lecture. His interest in China soon proved useful, says Kirby: When he wanted to apply to transfer from his all-male Dartmouth College, at least temporarily, to a college with women as well, the reason given was that they had a China historian there with whom he wanted to study.

To Berlin on an airlift scholarship

After graduating from university, Kirby applied for an "airlift thanks scholarship" donated by the city of Berlin and spent a year at the Free University. It was the 1972/1973 academic year, and here too Kirby encounters Chinese history rather unintentionally. He attended a seminar on Marx at the Otto Suhr Institute with political science professor Dr. Gesine Schwan. Among the 15 students, he says, were supporters of six different Communist splinter groups: KPD and SED party supporters, representatives of the KPD-ML, and supporters of the Albanian Communists; and: Maoists. China was hip at the time, especially among young leftists; however, Kirby says, people painted China as they would have liked it to be. The student Maoists knew little about the real history of China.

As an American to East Berlin

Kirby says his main task in the seminary was to travel to East Berlin on behalf of his fellow Communist students to get supplies of Marxist literature. As a U.S. citizen, he was allowed to go behind the Wall, something that was denied to many others from West Berlin.

Until he earned his doctorate, Kirby avoided committing himself to a region: he earned his doctorate in history, not sinology. His two professorial mentors at Harvard point in two different directions: Franklin L. Ford is a historian of German and French history, John K. Fairbank one of the leading historians of modern China at the time.

Book presentation in large circle: Peter Lange, Chairman of the Board of the Ernst Reuter Society (left), Professor of Sinology Mechthild Leutner (2nd from left), Prof. William C. Kirby and Prof. Peter-André Alt, President of the German Rectors' Conf

Image Credit: Michael Fahrig

Kirby combines the two almost Solomon-like in his doctoral thesis as well: it deals with German influence in National China, since China had better relations with Germany than with any other country in the world. He then applied to jobs in both German and Chinese history: he got a job in the latter, which, Kirby says, "focused the mind." He thought that was all right, he says, because he asked himself, "Do I really want to devote my life to studying 20th-century German history, as brutal and depressing as that is? Mind you, that was before I found out that Chinese history also has its extremely depressing chapters."

It is almost impossible to imagine that at that time there was nothing in China of an emerging superpower, of what would become the world's largest economy. Nor that in the 21st century a swelling trade war between the U.S. and China would put bilateral relations, academic exchanges and university cooperation to the test.

Kirby refuses to stand instrumentally by his administration as a China expert to avert China's dominance. He still sees himself as a mediator, speaking of "eminence" rather than dominance, defending China against Western prejudice while simultaneously defending the Chinese people against their own government. He can rave about Chinese entrepreneurs who founded a factory for tractor parts in 1969, simply to avoid starving, and turned it into the country's largest automotive supplier today with sheer perseverance, chutzpah and ingenuity.

Kirby links German university history with Chinese and American history

That may explain Kirby's latest book ("Empires of Ideas: Creating the Modern University from Germany to America to China"), which compellingly weaves together several of Kirby's interests and passions into a single narrative: the story of the modern research university. It begins in Berlin, following a blueprint laid out by Wilhelm von Humboldt, which makes the local university the leading academic institution in the 19th century. Only in the 20th century is it superseded in this by American universities, which combine the German postgraduate system with a British undergraduate education while maintaining the Humboldtian unity of research and teaching. In turn, Chinese universities are trying to outstrip them in the 21st century. Kirby thus combines German university history with Chinese and American, describing and analyzing his alma mater Harvard as well as the development of Freie Universität, which he first visited in 1972 and which awarded him an honorary doctorate in 2006. The whole thing is not only instructive, but also entertaining, because Kirby, as always, combines meticulousness with irony. His curiosity seems inexhaustible, as does his insistence on how essential learning from one another, mutual exchange, is, be it between teachers and students, be it between universities or even entire cultures.

At the invitation of the Ernst Reuter Society and the Confucius Institute, based at Freie Universität, William C. Kirby presented his new book to a wider audience at the Henry Ford Building in mid-December 2022.