Deciphering the Stories behind Art

Religion and literature are the key to understanding Islamic art, says distinguished art historian

Apr 09, 2021

Wendy Shaw, a professor of art history at Freie Universität, is calling for a new way of perceiving “Islamic art.”

Image Credit: Bernd Wannenmacher

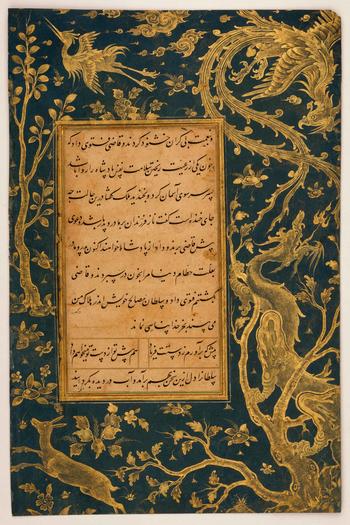

A dragon and a simurgh – a mythical creature similar to the phoenix – adorn the page of this elaborately illustrated, 16th century edition of a classic of Persian literature, the twenty-second story from the “Gulistan” or “Rose Garden” cycle by Sa’di, composed in the 13th century. According to Berlin’s Museum of Islamic Art, in the Chinese tradition the dragon and simurgh represent happiness and eternal bliss.

But this piece of information doesn’t answer a very simple question. Why were these mythical creatures included in the Persian manuscript at all? “Those who are familiar with Persian culture will know that there’s more than meets the eye here – it isn’t just a mere decorative element or a Chinese-style bird,” says Wendy Shaw. The professor of the art history of Islamic cultures at Freie Universität is calling for a new way of perceiving Islamic art. Her monograph What is “Islamic” Art? does not divide art into epochs or geographical regions, but instead focuses on stories and how philosophers, theologians, and poets have interpreted and retold them throughout the centuries.

For this new approach, Shaw’s book received the 2020 Albert Hourani Book Award Honorable Mention from the Middle East Studies Association of North America. The prize celebrates outstanding monographs from all research disciplines that engage with the Middle East, and Shaw’s book is only the second from the sphere of art history to receive the award. Her work was also awarded the Book of the Year 2021 in Iran..

Understanding Cultures in Order to Understand Art

The importance of a shared cultural canon for understanding art came into sharp focus for Shaw when she brought her young daughter to a museum full of European art from the Middle Ages. “Why are there so many naked men with their arms stretched out here?,” the four-year-old asked. She didn’t know what a crucifix was – which meant that she couldn’t understand the meaning of an image that is ubiquitous throughout the Western world.

“Most people in today’s world who go to an exhibition about Islamic art are just as uninformed,” says Shaw. “Museums have to compensate for these gaps in knowledge – but the typical information they provide about geographic and historical origins is not enough to provide any real illumination on the subject.”

At first glance, the illustration in the “Rose Garden” doesn’t appear to have much in common with the poem it accompanies, which tells the story of a deathly ill king who wants to sacrifice a boy to save himself. But the boy, trusting in God, faces his death with a smile, an act that touches the king so much that he realizes he is ready to die so that the boy can live. The aforementioned mythical creatures do not appear in the tale, but the images are imbued with a spiritual significance that indirectly link to the story’s religious moral and references to the Quran. “The illustration serves as a visual bridge between physical reality and the world of the story,” says Shaw, “It’s like taking a deep breath.”

The Fable of the Thirty Birds

Shaw’s book traces the long tradition of the simurgh throughout Persian literature. In the eleventh-century “Book of Kings” by the epic poet Firdausi, it is a mythical creature, but over time, in the writing of the Persian mystics, it took on a deeper meaning, symbolizing Platonic ideas of God. In “The Language of the Birds,” a well-known fable from the 12th century by mystic and poet Farid al-Din Attar, a large flock of different birds join forces to search for their legendary king, the simurgh. Only 30 birds survive the treacherous journey, before realizing that they themselves are “the king” – in fact, “simurgh” can also mean “thirty birds” in Persian.

From Sa’di’s Gulistan. Illustrated manuscript dated to between 1526 and 1530

Image Credit: bpk Berlin / Museum of Islamic Art, SMB / Jürgen Liepe

This story is often interpreted as a metaphor for democracy, says Shaw, but we have to look at it first and foremost from a theological standpoint; the evasive simurgh is a symbol for the impossibility of representing the divine in earthly terms. While visual representations are not generally prohibited in Islam, as is often assumed in the Western world, they do take on a different role than in the European tradition.

Not All Cultures Separate Art and Religion

Shaw explains that Islam is a quintessential part of this culture, yet the Quran and other religious texts are rarely used as references in understanding its art. Even the work of the great poets, such as Sa’di, Attar, Nizami, and Rumi, is considered by many art historians to be too vague. “However, poems tell us at least as much about the meaning of objects as the political context,” says Shaw.

And then there are the blind spots that afflict Eurocentric academia. European hegemony has made Western modernism a global standard by which everything should be judged. However, many modern and secular ideas, particularly the separation of art and religion, do not apply to premodern and Islamic cultures.

“Art history can come across as rather abstract. But research in the field is all about intercultural communication – especially when it comes to finding out how we can learn from each other,” says Shaw. Raised in Los Angeles, Shaw comes from a family with eastern European Jewish and Turkish roots. In fact, hardly any generation of her family has ever stayed in the place of its birth.

“Stories don’t ask who their audience is”

Berlin is home to one of the world’s largest collections of Islamic art, explains Shaw, allowing a way of accessing the cultural traditions of Islam that is completely different to the stereotypical narratives we see in the media. Shaw also recommends reading the literary classics, as literature is often the best mediator between cultures: “Stories don’t ask who their audience is.”

This text originally appeared in German on February 20, 2021, in the Tagesspiegel newspaper supplement published by Freie Universität.

Further Information

Professor Wendy Shaw, Freie Universität Berlin, Department of History and Cultural Studies, Institute of Art History, Email: wendy.shaw@fu-berlin.de