Detective Work on Behalf of Art

Researchers from the “Degenerate Art” Research Center unravel the fate of works of art seized during the Nazi era

Oct 30, 2013

Ostracized: Wilhelm Lehmbruck’s bronze statue “Große Knieende” (Large Kneeling Woman), was in the exhibition of “degenerate art” in 1938.

Image Credit: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Zentralarchiv

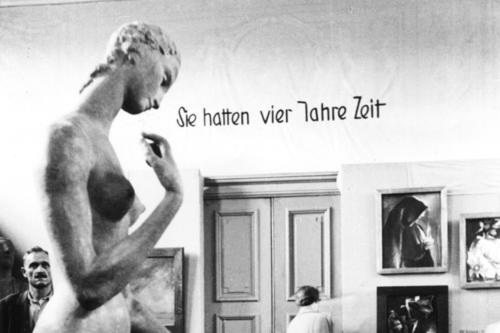

Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels (light-colored coat) visited the 1938 exhibition "Degenerate Art."

Image Credit: Bilderdienst Süddeutscher Verlag

Wolfgang Wittrock would like to lay one myth to rest: The proceeds from sales of “degenerate” art did not significantly add to the Nazi regime’s war chest. “They couldn’t have bought more than two tanks with it,” says Wittrock, the founder of the “Degenerate Art” Research Center at Freie Universität Berlin.

In 1937 and 1938, the Nazis seized about 21,000 modern sculptures, paintings, and works of graphic art from museums and public collections, selling some of them to foreign buyers in order to obtain foreign currency. The modern artworks deemed “degenerate” included pieces by renowned artists such as Otto Dix, Max Beckmann, and Franz Marc. What, exactly, the term means is not always clear. “All works that had a non-naturalistic form or style were considered degenerate,” explains Meike Hoffmann, the Research Center’s project coordinator, who holds a doctorate in art history. “The same was true if the color scheme was unnatural in the eyes of the Nazis, or for works with themes touching on social criticism,” she adds.

The “Degenerate Art” Research Center at the Art History Department of Freie Universität Berlin has been tracking these works since 2003. Professor Klaus Krüger took over as project manager in 2007. Now, right in time for the center’s ten-year anniversary, information on the fates of more than 10,000 works has been made available online. “We know the exact whereabouts of approximately 4,000 works,” Hoffmann says.

After they were seized, the banned works of art were taken to storage sites, such as the Viktoria-Speicher warehouse on Köpenicker Strasse, in Berlin’s Kreuzberg district. Some of the works the Nazis deemed saleable were offered for sale on the international art market. Unlike looted art, the museums cannot call for the return of the works seized in 1937 today. “Because these cases don’t have to do with racist or political persecution of individuals, but removing items of public property, there are no restitution claims,” Hoffmann says.

While researchers have been able to reconstruct the fates of paintings by famous artists in great detail, tracking down works on paper and those by less well-known artists has been difficult in some cases. “Important information often comes purely by chance,” reports Andreas Hüneke, who has been studying Nazi policies toward art for almost four decades. Historical or current photographs often offer important clues. “The Research Center has an excellent reputation worldwide, so we also receive information from other countries,” says Wittrock, who has contacts in the international art scene.

The art detectives’ research is based on the Nazis’ own inventory of works seized in 1937 and 1938, which lists all works confiscated from German museums and public collections. The information registered includes the artist’s name, the museum of origin, and numbers noted on the back of each work that had been designated as “degenerate.” The Nazis did not always work carefully. “The information listed in the inventory of works seized often contains gaps, or it might even be incorrect,” Hoffmann says. As a result, it will probably be impossible to clarify what happened to every single work.

Students at the Art History Department of Freie Universität Berlin are also doing their share to help with the center’s detective work in the field of art history. There are currently 13 final projects on Nazi policies toward art and culture in progress at Freie Universität, ten of them dissertations.

Further Information

Dr. Meike Hoffmann, Freie Universität Berlin, Art History Department, "Degenerate Art" Research Center, Tel.: +49 30 838-54523, Email: meikeh@zedat.fu-berlin.de