Translation Reference, Cultural and Political Signal

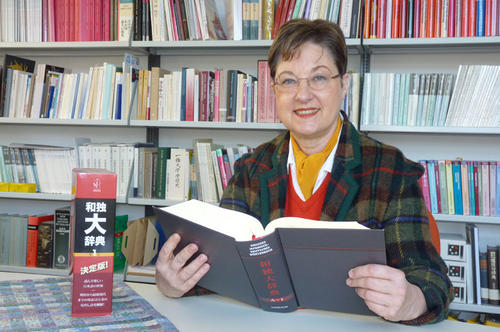

Researchers at Freie Universität Berlin are working on a major three-volume Japanese-German dictionary

May 06, 2013

Hijiya-Kirschnereit initiated the project in 1997, when she was working as the director of the German Institute for Japanese studies (DIJ), in Tokyo.

Image Credit: Bianca Schröder

Hijiya-Kirschnereit initiated the project in 1997, when she was working as the director of the German Institute for Japanese studies (DIJ), in Tokyo. “Many colleagues and I shared the opinion that we needed a comprehensive dictionary that compiles current vocabulary and terms from various specialized fields all in one place. We had known that for a long time, but it was not until then that we were in the right place with the opportunity to say, we have to take it into our own hands,” she explains. The last comprehensive Japanese-German dictionary, by Kinji Kimura, was published in Tokyo in 1937. It is considered outdated, and it only encompasses about a third as many terms as the new dictionary.

At the outset, the dictionary was a project of the DIJ, financed primarily through external funding. The sponsors included German and Japanese foundations as well as a number of private individuals and businesses from both countries. Lexicographic work got under way in 1999. Hijiya-Kirschnereit and her team first compiled a list of more than 200,000 keywords from Japanese lexicons on everyday language and specialized vocabulary – from youth slang to lexicons for construction, IT, or biochemistry – which then had to be narrowed down through further selection.

“The Japanese have documented their language very well, which is, of course, advantageous to us,” the scholar says. Alongside German equivalents to the Japanese words listed, the work also includes information on parts of speech and on variants used in reading and writing; it offers word origins, information on style and register, and typical usages.

One very special feature of the new concept is that it contains many sample sentences and idiomatic expressions culled from newspapers, advertisements, novels, and other sources to clarify a term’s use in context. Alongside its practical uses, the dictionary is also a signal in terms of academic and cultural politics, says Hijiya-Kirschnereit. After all, she says, German is still an important regional language, and one that is in widespread use in the research sector: “In my view, it is terrible for German to be undermined as a language of academia and research on the German side – and worse, by public funding on the German side.”

She agrees that researchers do have to speak English well, of course, but native speakers of German cannot simply be asked to use English as a route to Japanese. In some countries, Hijiya-Kirschnereit says, the Grosses japanisch-deutsches Wörterbuch is now considered a role model for other works, such as a new Japanese-French dictionary, a Japanese-Polish one, and a Japanese-Hungarian dictionary.

The project withstood one major setback. When Hijiya-Kirschnereit returned to Berlin in 2004, after eight years in Tokyo – she has been a professor at Freie Universität since 1991 – her successor in Tokyo stopped work on the project. For work on the dictionary to continue, a different institution would have to take over, since it would have been impossible to raise any further external funds without that kind of connection.

Luckily, the editorial team was given the opportunity to continue the project at Freie Universität. The university twice provided assistance when funds were running low while funding applications were in progress. In the meantime, the project’s finances have been secured with the aid of committed private funders in Japan and Germany as well as foundations to the point that the second of the three volumes is due to be published soon.

The project could not have come this far without special efforts by Iudicium Verlag, based in Munich. The publishing house invested considerable sums of its own and even made the first volume available to use free of charge on the Internet. Hijiya-Kirschnereit thinks that is a good idea and in step with the times, but she also defends the printed form. “If you translate professionally, it is a good idea to look at the entries before and after the term.” She is currently proofreading the second volume – and working on expanding the long list of supporters, so that it will be possible to publish the third volume as well.