A Champion of Independent Thinking and Astute Analysis

Hannah Arendt’s reflections on authoritarian regimes and the dangers of concentrated power and mass ideology are highly relevant today. Scholars at Freie Universität have been working on a critical edition of her complete works since 2018.

Dec 10, 2025

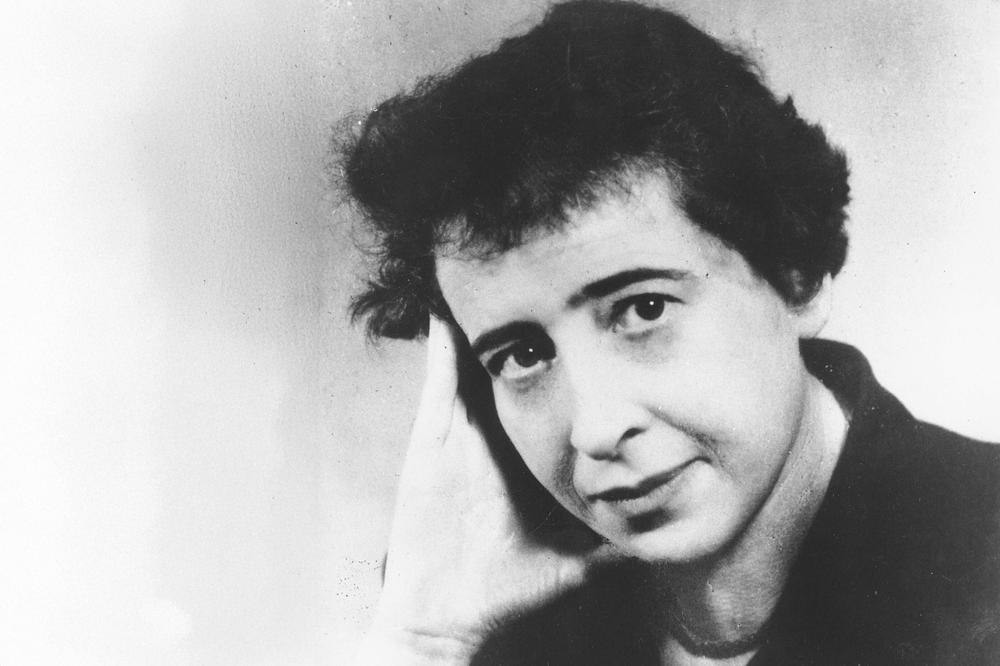

Hannah Arendt in 1954. After fleeing to the USA in 1941, she became a US citizen in 1951.

Image Credit: Erin Hooley, picture alliance / ASSOCIATED PRESS / Anonymous

Hannah Arendt’s contributions as a philosopher, publicist, and astute critic of twentieth-century totalitarian systems remain highly relevant today. Antidemocratic, authoritarian structures seem to be on the rise again worldwide, whether in the United States, Europe, or South America. Even people unfamiliar with Arendt’s work are likely to know of her major texts such as The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) or Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (1963), in which she covers the trial of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann. Her observations on National Socialism and Stalinism demonstrate how dangerous the concentration of power and mass ideologies can be for individuals and for democracy.

Resistance against the Nazi Regime

December 4, 2025, marks the fiftieth anniversary of Hannah Arendt’s death. Born in 1906 to Jewish parents in Hanover and raised in Königsberg, the city of Kant, Arendt became interested in philosophy at an early age. In 1924 she enrolled at the University of Marburg, where she studied under Martin Heidegger. She continued her studies in Freiburg and Heidelberg, earning her doctorate by the age of twenty-two. Her doctoral advisor was Karl Jaspers, with whom she maintained a lifelong friendship.

Arendt recognized the dangers of National Socialism early on and considered emigration even before the Nazis seized power. However, she stayed in Germany at first and became politically active as a Jew and opponent of the Nazis. From the start she began documenting the Nazi persecution of the Jews for the Zionist Association of Germany. In 1933 she and her husband fled the Nazis to France. Later she fled to the United States with her second husband.

People in front of the courthouse in Jerusalem, where the trial against the former SS-Obersturmführer Adolf Eichmann took place in 1961.

Image Credit: Picture Alliance / dpa

Hannah Arendt did not consider herself a philosopher, but rather a political theorist. For Arendt politics, like human society in general, is a space characterized by plurality, free will, and dialogue. She argued that we need a diversity of opinions and perspectives in order to make sound decisions. Today these basic tenets are at risk. Skepticism toward plurality and an unwillingness to engage in dialogue are growing in this age of social media bubbles and cancel culture judgments. When opinions clash, the differences seem insurmountable.

Updated Website

The website Hannah-Arendt-Edition.net highlights the current relevance of Arendt’s ideas and provides information and access to the ongoing project concerned with publishing and digitizing her complete works as a critical edition. Scholars at Freie Universität are in charge of the work on this edition, which began in 2018. The edited works are available both in print and in freely accessible digital form. Several volumes are being added each year.

This new edition presents all of Arendt’s works published during her lifetime: monographs, essay collections, articles, and interviews. In addition, it includes thousands of pages of unpublished documents from her literary estate in their original languages, including typescripts, notes, drafts, and revisions. Altogether approximately 21,000 pages of books, essays, and manuscripts/typescripts were processed for this edition.

The files on the website offer a unique glimpse into Arendt’s thought, writing, and revision processes. The notes scribbled in the margins or pasted into the texts along with other crossed-out passages give an impression of looking over the author’s shoulder as she is writing.

The editors emphasize that the digital content stands on an equal footing with the printed volume, while at the same time providing additional information. “The hybrid form offers entirely new possibilities, especially for researchers. It includes documents that would not be possible to reproduce in the printed edition and allows for direct comparisons of text versions. This makes the genesis of individual works more comprehensible,” explains Anne Eusterschulte. A professor of the history of philosophy at Freie Universität, Eusterschulte leads the international, interdisciplinary team of editors along with several researchers from literary and media studies, political theory, and history: Eva Geulen, Barbara Hahn, Hermann Kappelhoff, Marcus Llanque, Patchen Markell, Annette Vowinckel, and Thomas Wild. In addition to researchers based at Freie Universität Berlin and various other German academic institutions, the team also includes members of universities in the United States.

Arendt lived in New York City from 1941 until her death in 1975. During that time she also wrote her works in English. German studies scholar Hannah Gerlach explains, “Arendt wrote many of her works in both English and German. One version is not simply a translation of the other, but rather, each edition stands on its own in a certain sense and sets its own emphases.” Gerlach and her colleague Ingo Kieslich coordinate the long-term project at Freie Universität. It is funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG). About fifty researchers are involved.

Hannah Gerlach (left) and Ingo Kieslich (right) discussing details about the edition.

Image Credit: Bernd Wannenmacher

Observations on Evil

In early 2026 The Origins of Totalitarianism will be published in several volumes, and a new edition of Eichmann in Jerusalem is scheduled for 2027. Some sixty years after its initial publication, Arendt’s observations about evil in the book about Eichmann continue to spark controversial debate. In early November 2025, an international group of researchers gathered at the Topography of Terror Documentation Center in Berlin to discuss the book and its impact as part of the critical edition of Arendt’s work. They discussed ruptures in her thought, the role of bilingualism in her work, the ongoing controversy surrounding the concept of the “banality of evil,” and the contemporary relevance of the new edition. The results of the conference are being incorporated into the new edition.

In 1961 Arendt traveled to Israel to attend the trial of Adolf Eichmann, who under Hitler was responsible for organizing the deportation of Jews and was thus complicit in the murder of millions of people. Arendt observed how Eichmann presented himself in the courtroom: as a functionary of the Nazi killing machine who, like many other perpetrators, carried out his deeds on behalf of the regime as a respectable, meticulous civil servant. Based on her observations, Arendt wrote a series of essays for The New Yorker, which was later published as a book.

According to Hannah Arendt, evil is often not the result of extreme malice, but rather comes from an inability to think independently and to reflect critically on one’s actions. Her coinage of the “banality of evil” met with a great deal of harsh criticism right after the book was published. Critics said that it trivialized the murderers and mocked the victims. The conference participants discussed this criticism as well as Arendt’s perceptions of the Jewish witnesses at the trial, the possibilities of legal retribution for the Shoah, and the international reception of the text. Lisa-Maria Renner, one of the co-editors of the new edition, pointed out that it became very clear that Eichmann in Jerusalem has lost none of its relevance. She notes, “The discussions revealed that Arendt’s observations extend far beyond the historical case of Eichmann. If we read or reread the work today, we feel compelled to reflect on the meaning of responsibility, judgment, and the dangers of thoughtlessness.”

In his opening address at the conference, Israeli historian Tom Segev spoke in the same vein. He offered the audience not only academic insights, but also shared personal memories. As one of the last remaining scholars who had met Arendt herself, he talked about the tensions that the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem had triggered in Israel. Furthermore, he described the significance that Arendt’s book still has in Israeli collective memory. His words combined historical distance with an almost tangible closeness to Hannah Arendt and her intellectual movement at the beginning of the 1960s, a time when speaking about the Shoah was just beginning, cautiously and tentatively.

This article originally appeared in German in the Tagesspiegel newspaper supplement published by Freie Universität Berlin on November 29 , 2025.