Gravestones and “Stolpersteine”

Historian Hanno Hochmuth has documented the stories of Jewish families with the help of students from Freie Universität Berlin

Mar 11, 2025

Descendants of the Najman family with Hanno Hochmuth (second row, left) on October 11, 2022 at the laying of the “Stolpersteine” (stumbling stones) at Choriner Strasse 12.

Image Credit: Personal collection

On October 9, 2022, six Stolpersteine were laid in a poignant ceremony. Dominique Linchet and ten other descendants of the Najman family traveled to Berlin from the USA, Belgium, and Argentina to attend the laying of the Stolpersteine for their ancestors who were persecuted under the National Socialist regime. While Gunter Demnig inserted, grouted, and polished the Stolpersteine in the pavement, Petra Gutsche read out the biographies of the Najmans, symbolically bringing back to life the names engraved on the Stolpersteine.

Gravestone Business

The tailor David Najman was born in 1882 in Żarnowiec, near Gdańsk, and married Feigla Grubner who was born in 1879 in Chrzanów, near Kraków. Mr. and Mrs. Najman first lived together in Kraków, where their three sons were born in the following years: Leo in 1909, Heinrich in 1911, and Michael in 1912. Their fourth and youngest son, Samuel, was born in his mother’s birthplace in 1914.

That same year, the Najmans moved to Brno and then on to Berlin after World War I. Like many Jewish families, they fled the political upheavals in Central Eastern Europe after the division of the Austrian Empire, and emigrated to Germany since it was supposedly safer and more stable. David Najman was listed for the first time in the Berlin address book in 1921, under the name Neumann. He lived with his family of six at Choriner Strasse 12 in the Prenzlauer Berg district.

The Berlin address books also reveal that David Najman gave up his original profession and opened a gravestone business at Hirtenstrasse 11a in 1934. David Najman ran the business together with his eldest son Leo, while his sons Heinrich and Michael worked as stonemasons. On Hirtenstrasse, not far from the Volksbühne theater, they had many customers who wanted their loved ones to have a Jewish burial.

There are several gravestones from the Najman workshop in the Jewish cemetery in the Weissensee district in Berlin. This includes, for example, in plot B6, the grave of David Biegeleisen (d. 1937 in Berlin), who was born in 1893 in Chrzanów, the same small town (now in Poland) where Feigla Najman was born. The people from Chrzanów also kept in touch in Berlin and held Jewish funerals for their relatives.

Students of the master’s degree program in Public History in front of a grave at the Jewish Cemetery in Berlin-Weissensee, November 2024.

Image Credit: Hanno Hochmuth

A Deeply Melancholic Place

The Jewish Cemetery in Weissensee is a veritable necropolis that bears witness to the diversity and richness of Jewish life in Berlin in the past. Unlike in Christian or communal cemeteries, the graves were never reallocated and have miraculously survived the passage of time.

More than 116,000 gravestones stand close together and bear witness to the former Jewish population of Berlin, which was still 172,672 people in 1925. On the gravestones touching dedications commemorate the deceased. But since the Holocaust, there have been almost no relatives or descendants remaining in Berlin to look after the graves and only a few have been restored. The cemetery is simply too large to manage. Vast sections have been left to nature, where tall trees now tower over the seemingly endless burial plots and ivy-covered gravestones. Time seems to stand still in Weissensee, making it a deeply melancholic place.

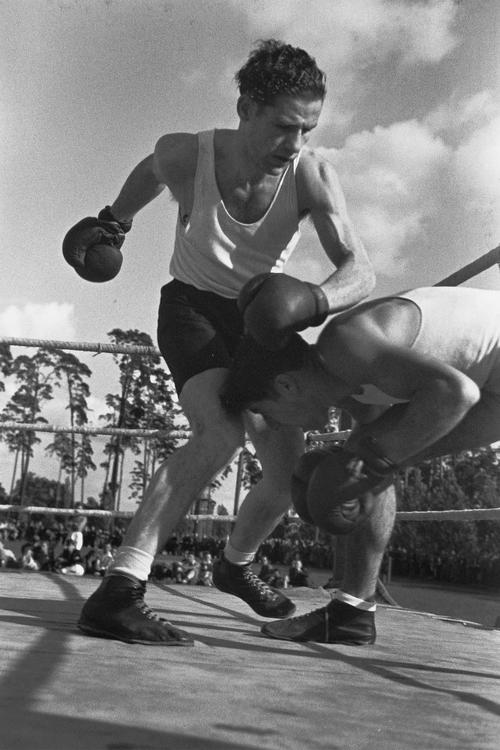

Samuel Najman (left) during a boxing match at the International Football and Handball Lightning Tournament of the Jewish Sports Club of Berlin (JSK) in August 1936.

Image Credit: Jewish Museum Berlin inv. no. FOT 88 500 98 021

The Najman family was not allowed to find their final resting place in the Weissensee Cemetery. The Nazi regime increasingly restricted their daily lives. Their youngest son, Samuel, sought refuge in the Makkabi Berlin boxing club.

On December 27, 1937, Samuel Najman was picked up by two Gestapo agents and taken to the Berlin police headquarters on Alexanderplatz for questioning. In January 1938, he was charged with passport forgery. Perhaps he had tried to forge passports for his parents, who as “stateless persons,” were unable to leave the country at all. In September 1938, the District Court of Berlin sentenced Samuel to six months in prison for “two counts of simple forgery of documents.”

Samuel did not serve out his sentence. Instead, at the end of October 1938, he and his parents were deported across the Polish border to Zbąszyń (Bentschen) by the Nazi authorities as part of the infamous “Polenaktion” (Polish Action). David, Feigla, and Samuel Najman were among the at least 17,000 Jewish people who had originally emigrated from Poland and were then suddenly deported as “stateless persons.”

With the Polish Action, the German authorities wanted to preempt the Polish government, which intended to close the borders to the German Reich, in order to stop accepting any more refugees. The Najman family became victims of an inhumane deportation policy. Their forced “remigration” was a brutal process, just as each deportation was and still is today.

David and Feigla Najman moved on to Tarnów, where they found shelter with relatives. But their Nazi persecutors caught up with them again with the German invasion of Poland. A ghetto was also set up for the Jewish population in Tarnów. The trail of David and Feigla Najman ended there in 1940.

Their son Samuel, however, fled from Poland to Belgium, where he was able to stay in hiding during the German occupation and survived the persecution. His three older brothers also miraculously managed to escape from Nazi Germany. Leo emigrated to England via Switzerland. Heinrich and Michael fled to Argentina via France and Uruguay, where they ran a gravestone business outside Buenos Aires near the Jewish cemetery at La Tablada. According to the Linchet family, Leo died in Israel in 1962; Michael and Heinrich died in Argentina in 1968 and 1980, respectively; and Samuel died in 1986 in Germany, where he had returned at the end of his life.

10,000 Stolpersteine in Berlin

Stolpersteine have also been laid in Choriner Strasse for their four sons, since the Stolperstein Project includes all persons persecuted by the Nazi regime, even those who managed to escape. The sons’ stones form a row below the stones of their parents, who were presumably murdered in the Tarnów ghetto in 1942.

Although the inscriptions on the small (10cm x 10cm) Stolpersteine cannot hold anything more than the names, years, and locations, they have become places of decentralized individual remembrance far beyond Berlin. Around 80,000 Stolpersteine have been laid worldwide since 1996: over 10,000 in Berlin alone. This is of course only a fraction of the people who faced persecution by the Nazi regime for racial, religious, or political reasons.

As part of a seminar in the Public History master’s degree program, the students worked together with the Prenzlauer Berg Stolpersteine Initiative to uncover some remarkable and distressing family stories. Based on this research, twenty more Stolpersteine will be laid next year in Prenzlauer Berg. They will keep the memory of these persecuted people alive.

Further Information

Dr. Hanno Hochmuth is Executive Manager and Research Fellow at the Leibniz Centre for Contemporary History Potsdam and a lecturer in the Public History master’s degree program at Freie Universität Berlin. The historian tells the story of the Najman family in his book Berlin. Das Rom der Zeitgeschichte (Berlin: The Rome of Contemporary History)