Much Noise about Isopods, Snails, and Earthworms

Soil ecologist Matthias Rillig invites artists to visit his laboratory at Freie Universität. They listen to what is going on in the soil.

May 25, 2022

Silence? Are you serious? Like the sea and the air, soil is also full of sounds.

Image Credit: pixabay

What sounds do mushrooms make as they grow through the ground? Matthias Rillig, a professor of soil ecology at Freie Universität Berlin, had never thought about this until the French artist Karine Bonneval approached him about it. “I couldn't get the question out of my mind,” says Matthias Rillig, “and finally it led me to a whole new field of research.”

Sounds and Vibrations Provide Information for Animals in the Soil

In 2016 Karine Bonneval wanted to sit in on Rillig’s working group’s laboratory and inspired him to listen to the soil. Rillig particularly liked one of her sound installations. “It was a kind of carpet made of soil, with clay tubes protruding like fruit. They served as listening stations for the sounds of the animals in the soil,” Rillig recalls. Together with the artist and a colleague, he published an article in a science journal on the role that sound or vibrations could play as a source of information for organisms in the soil. Rillig reports that this was a new perspective for him because he had previously assumed that it was quiet and dark in the soil and that organisms communicate primarily through the exchange of chemical signals.

After this productive collaboration, Rillig began regularly inviting artists to his working group, including the Slovenian artist Saša Spačal, who in her series “Myco Mythologies” explored what humans can learn from fungi about cross-species survival through inclusion and care. Rillig says that many members of his team are enthusiastic about it.

A Common Language for Art and Science

Together Rillig and the artists evaluated the experiences with artists in residence and for an article in a science journal, they summarized these experiences with ten rules that can contribute to the success of this type of project. Rule number one: the researchers and artists should be open to sharing their ideas. Rillig points out that artists are researchers of art and as a scientist he needs to respect their world view, their working methods, and their results, in order to gain new insights. He says, “That works best when we talk to each other, work together, get to know each other well, and in the process, find a common language.”

Other working groups in the Department of Biology, Chemistry and Pharmacy are now also interested in the concept and are preparing to collaborate. The department administration supports these types of projects with a subsidy of up to 5,000 euros each.

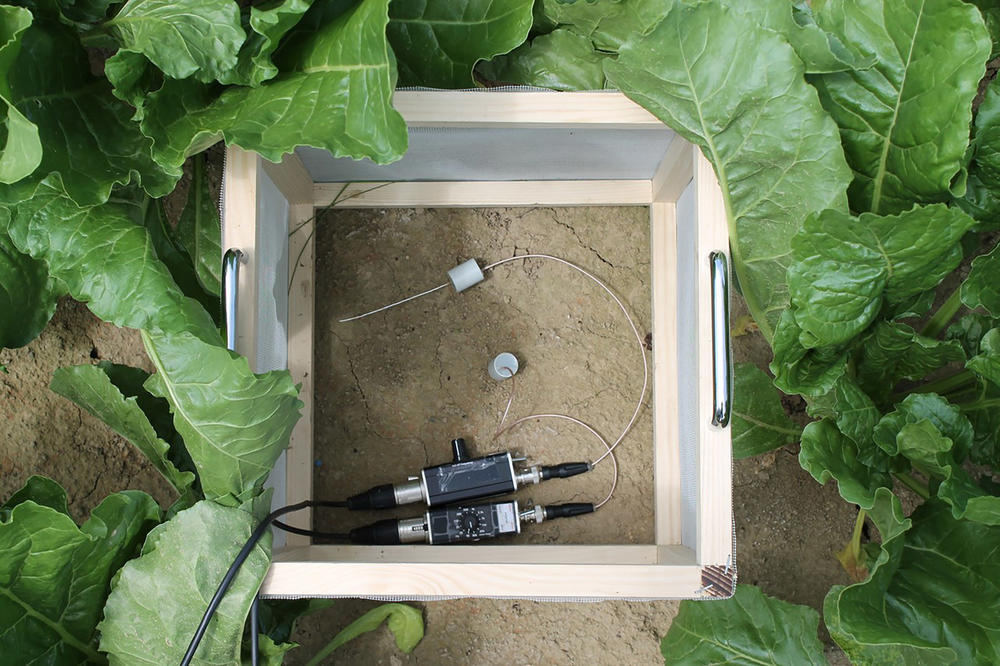

The scientist and artist Marcus Maeder can use probes to record noises in the ground.

Image Credit: Marcus Maeder

Art and Philosophy Meet Environmental Science

Marcus Maeder, a Swiss researcher, is a new guest in Rillig’s laboratory. Maeder studied fine arts and philosophy and is currently writing a doctoral thesis in environmental system sciences at ETH Zurich. He is also doing research on acoustic ecology at the Zurich University of the Arts. Biologist Rillig says, “We are learning from him how to record, amplify, and reproduce sounds in the ground so that we can play them back in a controlled form in laboratory experiments.” With special contact microphones that can be inserted into the ground more or less non-destructively and function like an antenna, Maeder recorded what a passing tractor sounds like in the ground. In a controlled environment, soil samples are exposed to the noise several times over a defined period of time. Then the scientists measure whether the noise has an effect on decomposition processes and biodiversity in the samples.

How Do Ants Sound?

In another experiment highly sensitive microphones record how the vocalizations of ants, springtails, and other animals change in response to the tractor noise. Maeder says that there are no final results yet, but it looks as if the small animals stop for awhile after the disturbance and no longer communicate acoustically with each other.

Maeder and Rillig suspect that the activity and diversity of the macro- and meso-fauna in the soil suffer from noise, such as the noise from highways, airports, construction sites, and agricultural machinery. If this is the case, noise pollution would be another factor in global change in our environment. Rillig points out, “We are only at the very beginning of this field of research, but we know the effect of noise pollution in the oceans and in the air. Why should it be any different in the ground?”

The Most Important Tool: The Amplifier

The greater the biodiversity, the better soil can fulfill its functions, such as breaking down dead organic material and producing nutrients for the production of plant-based food. Mites, insects, springtails, earthworms, snails, centipedes, and isopods (so-called primary decomposers) break down material so that microorganisms can use it. “If these soil animals were missing, our carbon cycle would be different,” explains Maeder.

In the coming year, Maeder would like to exhibit a sound installation at the Academy of Arts in Berlin that would make it possible to experience changes in biodiversity in the soil acoustically. The artist says his most important tool is the amplifier. In order to hear the sounds of the animals in the ground, he has to amplify them by a factor of 1000. “This makes things seem very close, and there is a moment of intimacy.” In this way, art and science are able to demonstrate that soil is extremely lively and sensitive to human influences.

Detecting Acoustic Signature of Soil Animals with Artificial Intelligence

Another joint project between Maeder and Rillig’s working group has to do with automatically recognizing the acoustic signature of soil animals. “We record the sounds of individual soil animals, such as earthworms, springtails, isopods, and ants, and train software to recognize the individual species by their sounds.”

This work is not yet complete, but Maeder can already use another method to acoustically measure how many different species of large and medium-sized animals are contained in a soil sample. To do so, he evaluates how many different sounds are contained in a recording and what dynamics they have. He then uses statistical methods to calculate an index for species diversity. Comparative evaluations using conventional methods for determining species diversity have shown that this works with astonishing precision.

This article originally appeared in German on May 8, 2022, in the Tagesspiegel newspaper supplement published by Freie Universität Berlin.

Further Information

Prof. Dr. Matthias Rillig, Freie Universität Berlin, Department of Biology, Chemistry, Pharmacy / Insitute of Biology, Email: rillig@zedat.fu-berlin.de

Related Publications

- Ten simple rules for hosting artists in a scientific lab, Matthias C. Rillig, Karine Bonneval, Christian de Lutz, Johannes Lehmann, India Mansour, Regine Rapp, Saša Spačal, Vera Meyer, PLOS Computational Biology, February 25, 2021

- The artist who co-authored a paper and expanded my professional network, Matthias C. Rillig, Karine Bonneval, Nature, Career Column, 27 February 2020

- Living Planet: The sound of soil, Audiobeitrag, Deutsche Welle, 27.02.2020

- Sounds of Soil: A New World of Interactions under Our Feet?, Matthias C. Rillig, Karine Bonneval, Johannes Lehmann, Soil Sytems, 2019, 3(3), 45

- Maeder, M., Guo, X., Neff, F., Schneider Mathis, D., & Gossner, M. M. (2022). Temporal and spatial dynamics in soil acoustics and their relation to soil animal diversity. Plos one, 17(3), e0263618.