Provenance Research to Trace Stolen Books

Two research projects were set up to clarify which books in the libraries of the Institute for Jewish Studies and the Botanic Garden of Freie Universität Berlin come from Nazi-looted property

Mar 21, 2022

Lisa Trzaska is researching the origin of a richly illustrated edition of Alexander von Humboldt’s travelogue on South America.

Image Credit: Bernd Wannenmacher

Sometimes it starts out with a feeling, says Stephan Kummer. “We go through the bookshelves systematically and on occasion a book stands out, and it looks as if we should check how it got here.” Kummer is a provenance researcher at the University Library of Freie Universität Berlin and a specialist in Judaic holdings. Even with his years of experience, good intuition, and perseverance for detective-like research, sometimes it takes years between this first feeling and the certainty that a book has found its way into the library illegally.

During the Nazi era, many millions of books were stolen in Germany and occupied Europe. Their owners were forced to sell, or their property was confiscated. Many were expelled or murdered. Books make up the bulk of the Nazi loot that is in German institutions today.

Provenance research in libraries is a complex field, requiring the researchers to work interdisciplinarily between history, politics, and culture. Books are mass-produced. It is only possible to turn them into pieces of evidence in the investigation of historical crimes and testimonies to individual fates by decoding the handwritten entries and the often lengthy research on library stamps or ex-libiris stickers.

One Million Books Need to Be Checked

At Freie Universität Berlin the Provenance Research Office headed by Ringo Narewski has been dealing with this work since 2013. All the findings of his team and its cooperation partners at other institutions can be accessed in the Looted Cultural Assets database, which has developed into a central tool for provenance research since it was launched in 2016.

Narewski estimates that it will be decades before the provenance of all the suspect books can be researched. In the University Library of Freie Universität alone, which includes all the institute and departmental libraries, around one million of the total of 6.5 million volumes would have to be checked.

“With the support of the German Lost Art Foundation, we can now systematically and completely check two important sub-areas,” says Narewski. So-called initial checks have shown that two libraries at Freie Universität contain a particularly high proportion of Nazi-looted material: the library of the Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum in Berlin and that of the Institute for Jewish Studies.

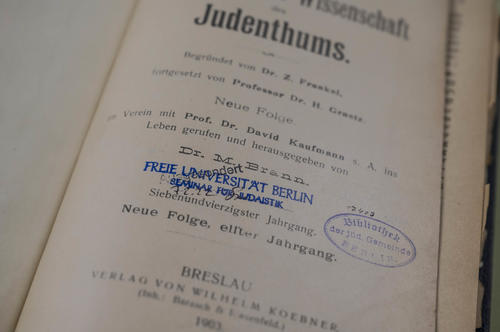

Returned recently: The library stamp of the Jewish community in Berlin put the provenance researchers on the right track.

Herbarium and Library Almost Completely Destroyed in World War II

The Botanic Museum was hit by a bomb in March 1943, and the herbarium and library were almost completely burned. The Nazi regime built up the stocks again even while the war was still on. The enormous sum of one million Reichsmarks was made available and made extensive antiquarian purchases possible in Germany and in occupied Europe. The library also received donations from Nazi institutions and botanists in the occupied territories.

Since April 2021 Lisa Trzaska has been researching the provenance of around 12,000 books, many of which are very likely from Nazi-looted property. “At least a third of these books come from Dutch antiquarian bookshops,” she explains. The Wehrmacht invaded the Netherlands in 1940. Many antiquarian bookshops were “Aryanized,” meaning that the property was confiscated from the Jewish owners. Others were forced to sell cheaply under pressure or abandoned their books when they fled. Trzaska points out that researching the provenance of these books is very difficult because so many factors overlap.

Alexander von Humboldt’s Travelogue through South America

Among the books that came to the Berlin Botanic Museum from the Netherlands during the war is a multi-volume, richly illustrated edition of Alexander von Humboldt’s travelogue through South America. “You can see that a rectangular bookplate was glued to the front of each book, but it was neatly ripped out of each volume,” explains Trzaska.

She is currently trying to find out who owned the valuable volumes and whether they were acquired legally. If it is Nazi-looted property, she will try to find the rightful owner.

Ringo Narewski (at left) heads the University Library’s Provenance Research Office. Stephan Kummer researches the provenance of the Judaistic holdings.

Image Credit: Bernd Wannenmacher

In the best case, the books can be returned. However, Stephan Kummer points out that researching legal successors, descendants, or relatives of the victims is also difficult. Since November 2020 Kummer has been researching the provenance of the University Library’s Judaic holdings. When the Institute for Jewish Studies was set up at Freie Universität in 1963 – the first in Germany – the library acquired most of the books through recommendations. Sellers were rarely noted, which is why Kummer is now reviewing 5,632 books published before 1945.

Puzzle Pieces Help Complete Family Stories

The researchers have already been able to solve some of the mysteries that had puzzled their colleagues for years, for example, that of a nondescript volume entitled “Guidelines for a Program for Liberal Judaism.” Someone had written “Grete Tichauer” in large, bold handwriting at the front, with “Lotte” underneath in pencil. Through intensive research, Kummer was able to find out that the two women came from Breslau and were murdered in the Auschwitz concentration camp. Contact with the Israeli aid organization Magen David Adom, whose employee called many people listed in the telephone directory, helped with the time-consuming search for living relatives.

In August 2021 they were finally able to return the book. “With our research and the books, we can give the heirs some pieces of the puzzle that can help to complete their family history,” says Narewski. Almost 80 years after the Shoah, the book is the family’s only memento of Margarete and Charlotte Tichauer.

This text originally appeared in German on February 26, 2022, in the Tagesspiegel newspaper supplement published by Freie Universität Berlin.

Further Information

Ringo Narewski, University Library, Provenance Research Office, Freie Universität Berlin, Tel.: +49 30 838 57470, Email: narewski@ub.fu-berlin.de