Following the Trail of Books

The Washington Declaration at 20: an interview with Ringo Narewski, head of the unit charged with restitution of items looted by the Nazis, following the meeting, in Berlin, of the “Provenance Research and Restitution at Libraries” taskforce

Jan 19, 2019

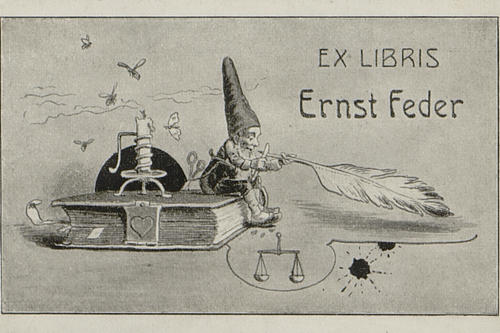

From the library of Ernst Feder (1881–1964), a writer and journalist who fled Germany in 1933. A book from his library (which had several thousand volumes) is now at the University Library. So far the library has been unable to give it to his heirs.

Image Credit: Universitätsbibliothek Freie Universität Berlin

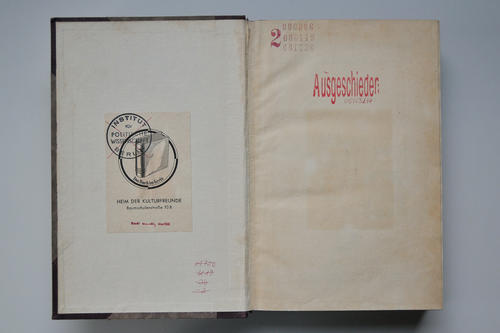

After 1945: Rudi Otto Georg Garski (1910–1985) fled to Berlin from the Soviet occupation zone in the late 1940s. His possessions were confiscated. Two of his books are now held by the University Library. His family did not wish to take them back.

Image Credit: Universitätsbibliothek Freie Universität Berlin

Ringo Narewski is in charge of a special body at the University Library charged with restitution of items looted by the Nazis. This unit has been working since 2013 to forge closer ties among similar projects in the local area.

Image Credit: Jenny Jörgensen

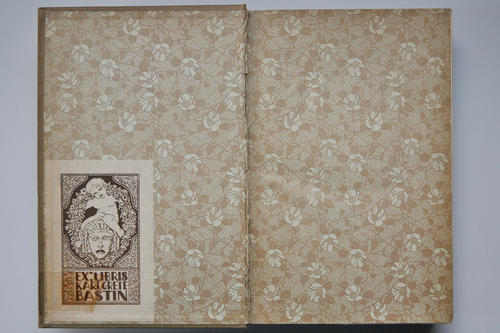

Dr. Karl Bastin (1882–1960) and Margarete Bastin (1883–1968) survived the Third Reich in hiding; their property was confiscated. Thus far, it has not been possible to identify the heirs to the two books now held by the University Library.

Image Credit: Universitätsbibliothek Freie Universität Berlin

The Nazis are known for looting art, but that wasn’t all. They also took countless books during the Third Reich. Many of them are still housed at libraries in Germany today. In 1998, Germany signed on to the Washington Principles, committing to return not only works of art, but also books to the families of their owners wherever possible.

To mark the declaration’s 20th anniversary, about 60 provenance researchers from the “Provenance Research and Restitution at Libraries” taskforce gathered in Berlin in late November to take stock of where things stand. The meeting was organized by the Central and Regional Library Berlin (ZLB), the Centrum Judaicum, and Freie Universität Berlin.

Mr. Narewski, you are checking the book collections of Freie Universität Berlin for items looted by the Nazis. How do you do this?

First, we look for books that were published before 1945, and then we see whether there are any indications in the books regarding their previous owners. Sometimes we find names, sometimes stamps placed by institutions or bookplates, little pictures people used to paste inside their books. If there are none of those things, we can compare the book to similar ones. That lets us find clues that the book used to be somewhere else.

All of that together helps us find out where books were before they came to be in the libraries at Freie Universität Berlin. From here, we try to research whether former owners of books had their property seized during the Nazi dictatorship and during World War II. If so, we start looking for family members of those whose possessions were seized, or successor organizations to the institutions whose property was confiscated.

What books are involved?

In general terms, all kinds: literature, novels, children’s books, scientific and scholarly works. For us, the focus is on scholarship. These are often very simple books, nothing special, and as a rule their financial value is low. But if we can turn them over to the owners’ descendants, they are sometimes the only objects that they have left from their parents, grandparents, or great-grandparents, who were expelled and murdered.

Can you tell us about someone you found?

In 2014, we found a bookplate in Hebrew in four volumes of a collection of the works of Heinrich von Kleist. The bookplate referred to Gerson Frohmann-Holländer, a Jewish stonemason from Frankfurt. His family, like all Jewish families, was persecuted by the Nazis for racial reasons. While his son remained in Germany from 1933 to 1945 and survived, his daughter, son-in-law, and granddaughter emigrated to New York in 1938 and 1939, escaping the Holocaust. They had to leave their belongings behind.

The persecution and escape were so stressful for Frohmann-Holländer’s daughter that she committed suicide in exile the very same year they fled the country. Her husband and their daughter spent a long time after the end of World War II trying to have her recognized as a victim of the Nazi terror and to obtain compensation for the injustice they had suffered. Our research finally led us to a great-granddaughter of Gerson Frohmann-Holländer. In 2017, we were able to give her back the books belonging to her great-grandfather that we had found in our collections. We got in touch via Facebook, incidentally.

How did the great-granddaughter respond?

She was thrilled. In addition to the books, we were also able to present her with the information we had compiled through our research on her family history. The descendants are very interested in that.

You met with a number of provenance researchers from various libraries in Berlin in late November. What did you discuss?

It became clear at the meeting just how laborious and time-consuming the individual research is, and that if we are to be able to do this, we need long-term financing and permanent, qualified staff for provenance research at public institutions. At libraries in particular, the number of books that need to be investigated is huge. Freie Universität alone has more than a million books published prior to 1945 that we need to look at. We have been able to check over 100,000 books and determine their provenance since 2014. More than 200 of them have been clearly identified as looted goods so far.

That doesn’t include the cases that are still unresolved, where we haven’t been able to do a final evaluation yet, or those where we don’t have anyone to contact for return purposes. That’s also not counting those where we were definitively able to say the books were not looted. We have also run across quite a number of items confiscated during the period after 1945, whether in the Soviet occupation zone or the former East Germany. We haven’t fully clarified yet how we are supposed to deal with these wrongful seizures. Intuitively, you’d like to proceed in the same way with these as with the confiscations from the Nazi era. Some cases are solved quickly, while others, like the Frohmann-Holländer one, take time.

What would you like to see happen in the future?

I’d like to see stronger ties beyond the library world, including internationally. Within Freie Universität, we are in the very early stages of cooperating with Meike Hoffmann, an art historian at the Research Center for “Degenerate Art.” Librarians, art historians, and archivists have not yet tapped into their full potential here – far from it. We are working in the same field, using the same research tools and methods, and it is not uncommon for our results to overlap. Those who collected art and were persecuted by the Nazis often also had a library, and that library was confiscated together with their works of art and other possessions.

In the long term, there is an urgent need to develop a joint database for provenance research at libraries, museums, and archives, where the research findings are logged and combined in detail. The goal of doing this would be to make the research more effective and minimize the work involved by pooling our knowledge. The cooperative Looted Cultural Assets database, which is operated not just by us, but by several libraries in Germany, combines our research findings. That means that at least for the library sector, we already have an excellent approach to this issue, and one that has achieved broad acceptance in the research community. But there’s always room to improve and expand, and the goal should be to have a shared research tool.

The interview was conducted by Amely Schneider. It originally appeared in German on December 20, 2018, in the campus.leben online magazine published by Freie Universität.

Further Information

Ringo Narewski, University Library, Nazi-Loot Investigation Bureau, Freie Universität Berlin, Tel.: +49 30 838 57470, Email: narewski@ub.fu-berlin.de