„Nun wollet ihr wiesen waß wier Esen und Trinken“

Historian Juliane Graf examines letters from Germans who emigrated to America in the 19th century. She received a Friedrich Meinecke Award for her work.

Apr 21, 2020

The development from an agricultural to an industrial society shaped Europe of the 19th century. Crises of hunger and starvation following crop failures worsened the situation, especially for people who had to live from agriculture. At that time, many of them followed their dreams of building up a new existence overseas – more precisely, in the USA. “Anyone who could somehow raise money for a ticket across the Atlantic looked toward emigration – an extremely daring undertaking at the time,” says Juliane Graf.

For her doctoral thesis, the historian analyzed around 180 letters from people who emigrated to the United States from areas of small German states between the 1850s and 1880s. They were addressed to relatives who stayed at home. In December 2019 Juliane Graf received the Friedrich Meinecke Award from the Friedrich Meinecke Institute of History at Freie Universität Berlin. The award is presented annually for an outstanding dissertation in history and cultural studies, which was submitted that year at Freie Universität.

People Wrote What Came to Mind

Many letters contain descriptions of everyday occurrences, as is the case with Adelheide Tapert, who wrote to her family on November 22, 1854, and reported on the eating habits in her new home: „nun wollet ihr wiesen waß wier Esen und Trinken / ob wier Kardoffel Klöse koch oder Datsch backen wir kochen Klöse / und Schopfebraden auch zu weilen Gänsebraden. in America ist die / Mode des Tages wierd 3 Mal zu äsen da giebts 2 mal Fleisch […]“ The emigrants also described experiences on their long trip to the new country and challenges facing emigrants.

For many emigrants, writing letters was a way to unload their emotions, says Juliane Graf: “People just started writing what came to mind.” On the other hand, sometimes they concealed uncomfortable things or glossed over facts. For that reason, when examining the letters, it is also important to take into account information from official sources such as death certificates and censuses. Juliane Graf suspects that many of the emigrants would not have written letters if they had not emigrated because, with one exception, the letters she examined were not written by people with university degrees. This is apparent in their linguistic characteristics. She says the letters were written in simple language, some in the dialect of the writer’s home.

Between Border Experiences …

Juliane Graf pointed out that she wanted to find out how the emigrants encountered the new and unknown. The theoretical basis of her work was the research field of academic scholarship on borders, so-called border studies.

First, she dealt with the actual political border that had to be crossed when entering the United States. Because the number of immigrants continued to rise in the course of the 19th century, the entry process was organized increasingly effectively by the U.S. authorities. At the same time, the entry regulations applicable at the beginning of the 19th century became increasingly stringent over the period from the 1850s to the 1880s.

Juliane Graf also dealt with social and cultural boundaries. She asked, “How did the emigrants encounter people who had a different cultural or ethnic background than themselves?” A majority of the letter writers, for example, did not support slavery, but as white Europeans, they enjoyed a favorable position, right from the start. “The dominant narrative of poor immigrants who made it in the U.S. is of course correct,” says the historian. Of course, it is important not to lose sight of the fact that in North America they encountered a society that systematically expropriated the country’s natives – a circumstance that ultimately also benefited the German immigrants.

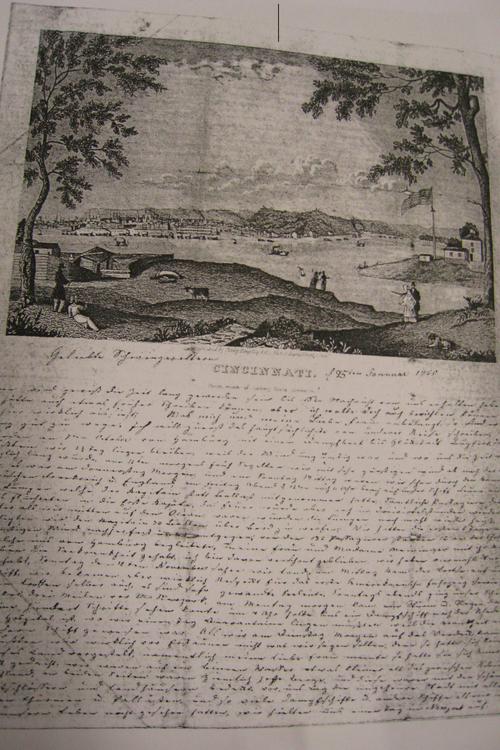

Letter from Friedrich Ehlers to his in-laws in Ribnitz, Mecklenburg-Schwerin, dated January 25, 1850. Friedrich Ehlers emigrated to Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1849 with his wife Caroline. He was Henriette Burmeister’s brother-in-law.

Image Credit: Forschungsbibliothek Gotha, NABS, I. Serie Nordamerika, B, Serie Burmeisters-Ehlers

… and New Opportunities

Juliane Graf was particularly struck by Henriette Burmeister, who emigrated to America with her finance. They got married right after their arrival. When it turned out that her husband drank and was violent, Henriette Burmeister left him with their children. She earned her own money with smaller jobs, learned English, and became independent. In the letters to her relatives, it becomes clear that the young woman experienced this as a liberating experience, says Juliane Graf. “Even when she got married again later, it was always important to her to be perceived as a ‘self-made’ woman.” Presumably, this would not have been possible in her old home at that time.

Seeds and Vocabulary Lists

The letter writing served not only the exchange of experiences. Material things also found their way across the Atlantic. If you missed German kale, your family sent you kale seeds. Transfer also went in the opposite direction: If the emigrants found a special type of clover, which was good for feeding cattle, they sent some plants to Germany so that relatives at home could also use the clover as feed.

“Another letter,” says Juliane Graf, “included a vocabulary list to show the family what progress had been made in the foreign language.” She did not find any photographs in the correspondence and assumes that the people in Germany who received the letters took the photos out and framed them or kept them separately.

History professor Bernd Sösemann from the Friedrich Meinecke Institute points out that due to the objects that were sent along, the letters could be examined as more than merely self-testimonials. The multidimensional evaluation is a special contribution to the history of German-American relations. Professor Sösemann said, “Juliane Graf’s work underscores the importance of civil-society interactions between Germany and the United States,” and he added, “In the current phase of increasingly fragile political relations between the two countries, this should not be underestimated.” Sösemann chairs the Friedrich Meinecke Association.

Questions Extending to the Present

In her scholarly work, Juliane Graf focuses mainly on the past, but she also deals with current issues. She points out that the perception of Germany as a so-called immigration country is relatively recent. This new concept led to questions about the origin of immigrants, their motives for coming to Germany, and last but not least, about the effects that immigration of people from other parts of the world has on German society.

“Such fundamental questions keep popping up – regardless of whether you are considering current migration processes or those of the 19th century,” says historian Graf. Although the type and infrastructure of communication has changed greatly – in the 19th century, people wrote letters, while today they send live videos and voice messages – one thing remains independent of the epoch: the need to communicate and the desire to exchange ideas.

The original German version of this article was published on March 17, 2020, in campus.leben, the online magazine of Freie Universität Berlin.

Further Information

- The letters that Juliane Graf examined come from the North America Letter Collection (Nordamerika-Briefsammlung, (NABS), which is part of the German Emigration Letter Collection (Deutsche Auswandererbriefsammlung Gotha, DABS). DABS also includes the Bochum Emigration Letter Collection (Bochumer Auswandererbriefsammlung, BABS), which was created in the 1980s under the direction of historian Professor Wolfgang Helbich at Ruhr-Universität Bochum. Due to the division of Germany, BABS only contains letters that could be collected in the German Federal Republic of the time.

- After German reunification, NABS was founded in the 2000s under the direction of Professor Ursula Lehmkuhl in cooperation with the Gotha Research Library, which had a regional collection focus in the areas of the former GDR.