Science Diplomacy Opens Doors

The Seminar for Semitic and Arabic Studies at Freie Universität Berlin hosted a discussion about the possibilities that science diplomacy offers. Instructors from the university have tested out this format in a joint project with Iraqi students

Aug 23, 2024

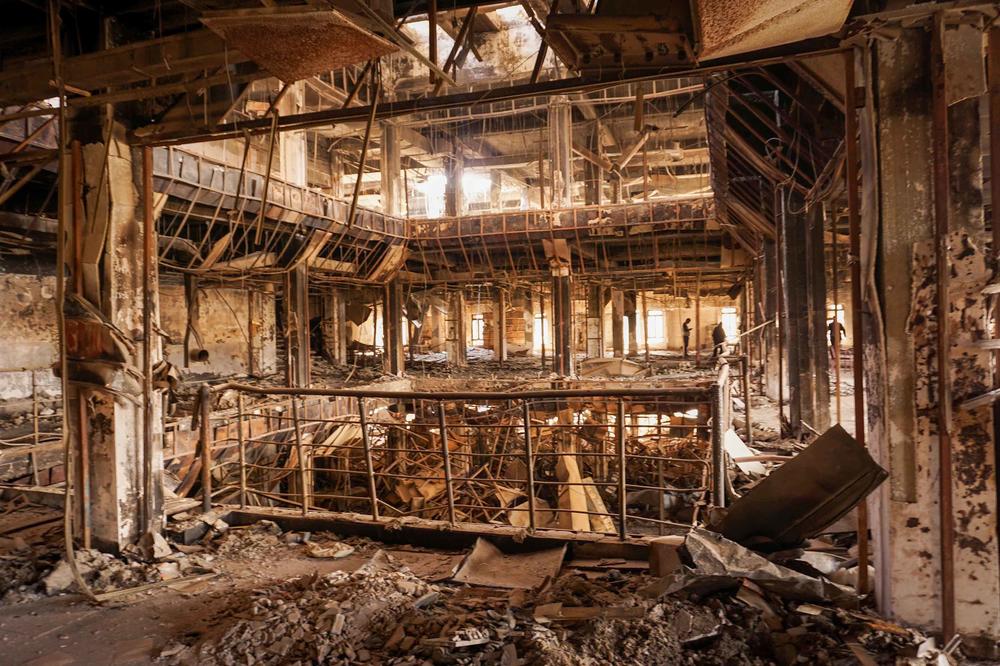

All that is left of the university library are its steel girders protruding out from the rubble. Regardless of what happened here, it is safe to say that no books could have survived this scale of destruction. This stark image of the University of Mosul’s destroyed library taken by the photographer and university lecturer Ali Al-Baroodi in November 2017 was used in the opening to Professor Heike Wendt’s talk “Science Diplomacy – What Can Universities Do in Times of Escalating Conflicts?” held in the Holzlaube building of Freie Universität Berlin on July 4, 2024.

Professor Wendt from the University of Graz, Austria, and other participants involved in the RESI (Rethink Education and Science in Iraq) project talked about their experiences as part of a discussion on science diplomacy. Instructors from Iraqi and European universities have been offering week-long workshops in a future conference format for Iraqi students each year since 2017. Wendt, who is an expert in empirical research in education, is particularly interested in the transformation of educational systems in conflict zones. Asking questions surrounding the role played by university partnerships is imperative in this area. “Science diplomacy is a way of exercising soft power in pursuing diplomatic goals,” says Wendt. “It can be used to build trust and establish relationships.”

Mosul University, which was founded in 1967, was once a place of great hope that attracted scholars from all over the world. The Gulf War of 1991 and the invasion of Iraq in 2003 – along with growing Islamic extremism – resulted in considerable instability and violence, which led to the deaths of many academics or forced them to leave the country. Three hundred scholars were executed between 2003 and 2007 as the country’s educational infrastructure was systematically destroyed. In the wake of ISIS’s defeat educators in Iraq have been working to re-establish international relations around the globe.

Mapping Lost Spaces

The idea to develop an interactive map of Mosul arose during a student conference in 2023, when professor of Arabic studies Isabel Toral (Freie Universität Berlin) and professor of history Konstantin Klein (University of Amsterdam) went to the city to teach Iraqi students about ancient and medieval metropolises in the Middle East. Discussions with the students landed on the topics of destruction and cultures of remembrance, culminating in the idea to produce a map with significant sites of remembrance. The “Memory Spaces: Mapping Oral History in Mosul” project is based at the Seminar for Semitic and Arabic Studies at Freie Universität Berlin and receives funding from the Gerda Henkel Foundation. Residents of Mosul can configure a digital map to include text, sound, video, and image files, contributing their personal memories of private residential buildings and other community buildings that were destroyed during the Islamic State’s occupation of the city from 2014 to 2017. They are also invited to share their memories of the battle to liberate Mosul launched by anti-ISIS forces. “Memory work may be the primary goal of the project, but students also want to reach people all over the world and show them their city as they remember it,” says Professor Toral. The pilot project has laid the groundwork for further cooperation between the three universities in Berlin, Amsterdam, and Mosul.

What else can be done to support academics in times of crisis? “We should be providing assistance in setting up archives, book inventories, and external data storage solutions so that research data is not lost,” says Wendt. Thanks to an initiative launched by Klein, a bus in Mosul was converted into a mobile library with an internet connection. The panelists agreed that one-on-one encounters and discussions are extremely important. “Over ninety percent of faculty at the University of Mosul have never been abroad,” says Wendt. Professor Elke Hartmann from the Institute of Ottoman Studies and Turcology at Freie Universität Berlin notes that differing ideas on the role of women can make cooperation more difficult. For example, sons of dignitaries are often nominated for trips abroad rather than better qualified women. This could be circumvented by looking for early-career female researchers to collaborate with on site.

Science diplomacy is also an important topic in eastern European studies. The full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine had ripple effects on the work carried out by the Institute for East European Studies at Freie Universität Berlin. “For many years its work was focused on carrying out research on and in Russia,” says Florian Kohstall from the Center for International Cooperation at Freie Universität Berlin. A number of joint research projects and exchange programs supported by the university’s liaison office in Moscow were suspended once war broke out. Soon thereafter, the liaison office itself was relocated to Tbilisi in Georgia. “This step was unavoidable because of Russia’s war of aggression and growing impositions on academic freedom in Russia,” says Kohstall. “But part of science diplomacy is keeping communication channels open, especially since academic cooperation thrives on long-term relationships. Naturally when geopolitical tensions arise we have to review university partnerships, but we also have to be able to withstand controversies. That is also why we tend not to engage in boycott campaigns in general.” As Toral concluded at the end of the discussion, “Science is a global good that we need to protect, especially in difficult circumstances. We will only be able to find solutions to the problems of our time if we work to support a global system of knowledge.”

The original German version of this article appeared in campus.leben, the online magazine published by Freie Universität Berlin.