Mushrooms Galore

The Botanic Museum in the Botanical Garden purchased a significant collection of mushroom books.

Mar 13, 2020

Numerous volumes of the mushroom collection on display in the Botanical Museum document the historical development of botanical illustration, e.g., this toadstool copper engraving from 1842.

Image Credit: Library, Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin

No roots, no leaves, no flowers. Mushrooms, those enigmatic spore carriers that have sprung from an underground network, lead a hidden life. Apart from powdery mildew on the rose or baker’s yeast on the refrigerated shelf, many mushrooms only can only be seen in a very limited period. Especially in the fall, they suddenly appear in diverse forms, but that only lasts briefly. Just as fast as they appear, they are gone again.

It is no wonder that until modern times, almost everywhere mushrooms have been associated with the devil or insanity. Mycology, or the science of fungi, took a back seat to the research on plants. The famous natural scientist Carl von Linné interpreted tiny germ hyphae of the fungal spores as worms and thus classified them with the animals in his Systema naturae published in 1776.

The Swede Elias Fries, also known as the “Linné of mushrooms,” is the founder of systematic mycology. His Systema mycologicum, published in several volumes beginning in 1821, marks the starting point of mycological taxonomy, which means that until today, only mushroom names that were assigned after the publication of this work are valid. The year 1821 also marks the start of a historical mushroom book collection that the library of the Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin (BGBM) acquired from the private collection of the antiquarian Christian Volbracht.

This acquisition will make the most important and extensive collection of books on mushrooms from 1821 to 1959 publicly accessible. The specialist field of mushrooms ranges from simple mushrooms to psychoactive, pathogenic, wood-destroying mushrooms to mushroom fairy tales, mushroom cookbooks, and works on the systematics of mushrooms. A large part of the collection consists of volumes that show mushrooms in all their splendor and thus reflect the development of printing techniques – from hand-colored copperplate engravings to multicolored stone prints and offset printing. “This important collection of literature on mushrooms is in good hands in our library,” said Thomas Borsch, the director of the Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin.

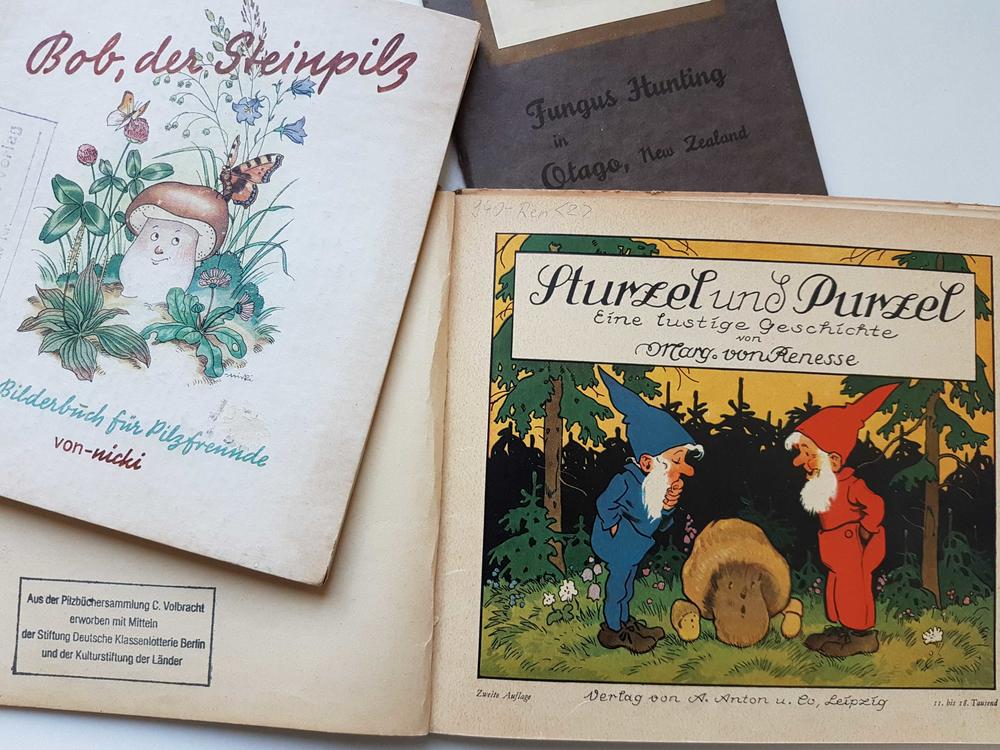

Sturzel and Purzel und Bob, the boletus – children’s books from the early 20th century.

Image Credit: Library, Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin

Teaching and research in mycology have a long tradition at Freie Universität: the Botanic Garden is home to the largest mushroom herbarium in Germany and has been offering free mushroom advice to citizens for 120 years. Due to losses suffered during wars, the library’s stock of literature on mushrooms, especially books from the 19th century, was greatly decimated, said Professor Markus Hilgert, Secretary General of the Cultural Foundation of the German Federal States. With the newly acquired collection, the Library of the Botanic Garden can now become one of the world’s most important libraries for literature on mushrooms. The Cultural Foundation of the German Federal States supported the purchase with 90,000 euros. In addition, the acquisition of the collection for a total of 270,000 euros was made possible through a donation from the Berlin Lotto Foundation and a contribution by the BGBM.

Andrea Tatai, deputy head of the library system at Freie Universität, described it as a “stroke of luck to acquire such a collection in one fell swoop.” It was also a way to fulfill the collector’s desire to preserve the collection as a whole. It was important for Christian Volbracht to know that the rare works in his collection were in good hands. “The number of bibliophile collectors is decreasng,” said the antiquarian. Therefore, he wanted to determine the future of his collection himself. He pointed out that the fact that the books are finding a place in the library of the Botanic Garden is “a nice reward for a long life as a collector.”

Christian Volbracht found his first mushroom book on his grandfather’s shelf. Using it, he roamed the steep slopes of Bad Harzburg in search of chestnut roebuck and bald Kremplingen. Years later, now a journalist at the German Press Agency, he exclusively spread the news that this Krempling can lead to fatal kidney damage. His involvement in mycology intensified, and he began to search for and collect old mushroom books wherever his profession took him. In Brighton, England, he asked an antiquarian whether he had books on mushrooms, “Do you have books on fungi?” He replied: “No, but I have fungi on books.” And indeed, mold was rampant in the booseller’s basement.

In order to finance his increasingly expensive purchases, he sent a first list of duplicates to other book collectors and mushroom lovers. Collecting and buying became trading and selling. Since 1996, Volbracht’s niche antiquarian bookshop MykoLibri can also be found on the Internet, where he will continue to trade books. Volbracht was spared the shock of standing in front of completely empty shelves. He still has more than 500 rare books from the 17th to the 19th centuries.

A chromolithography from 1872 about the most important mushrooms, drawn by Ernst Buschendorf.

Image Credit: Library, Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin

The period covered by the collection is extremely exciting for mushroom literature, said the director of the BGBM library, Norbert Kilian. On the one hand, mycological research boomed in the 19th century. On the other hand, a social interest in living nature was developing. As a result, a wide range of popular science literature emerged. Natural history and mycological associations sprang up like mushrooms.

Christian Volbracht included evidence of both lines of development – the emergence of an exact science and the tradition of participative amateur mycology – in his collection, which forms an important foundation, especially for the research of cultural and societal aspects of mushroom literature. In addition to the large color atlases with their detailed copper engravings and lithographs, Volbracht collected popular, historically interesting mushroom guides, which were intended to help mushroom collectors to distinguish edible mushrooms from poisonous ones. “In times of war, significantly more of these guides appeared than in quieter periods,” said Volbracht. Mushrooms were valued as the meat of the forest and as an important food reserve in times of war.

According to Norbert Kilian, one of the earliest examples of applied popular science mushroom books is François Cordier’s Guide de l'Amateur de Champignons. The volume was published in 1826 and, thanks to its small format, easy to take along on walks and into the woods. It is a comprehensive introduction to the usefulness of mushrooms. It also contained a description of the tinder sponge, which from the Stone Age to the middle of the 19th century, was the most suitable material for lighting a fire – hence the expression “burns like tinder.” To remain affordable, the 250-page reference book contains just eleven color plates.

Colored images were precious rarities before the development of inexpensive printing techniques. Because making the illustrations was often a tedious business, Claude Gillet had his children help him paint the 900 plates of his standard work Champignons de France. The illustrations in M. C. Cooke’s Illustrations of British Fungi are unique. Published toward the end of the 19th century, the book has 1200 chromolithographs. On a picture of a Coprinellus micaceus, often called mica cap, shiny cap, or glistening inky cap, there are wafer-thin pieces of glass that glitter like sugar crystals on the mushroom caps.

But the collection includes much more. In addition to the conspicuous large mushrooms, there are countless tiny fungal organisms that are mostly neglected in the literature. One of the first works that dealt with the microscopic world of fungi was August Corda’s Pracht-Flora europaeischer Schimmelbildungen that was published in 1839. On 25 magnificent panels, immensely enlarged mold is depicted as a fantastic mixed forest or as a flora of strange stars. This rarity, which the contemporary botanist Matthias Schleiden criticized as “senselessly wasteful” is part of the Volbracht collection.

This article originally appeared in German on March 12, 2020, in the campus.leben online magazine published by Freie Universität.