Politics, Protests, Personalities

The John F. Kennedy Institute for North American Studies was founded in 1963 by the political scientist Ernst Fraenkel.

Image Credit: Bernd Wannenmacher

When John F. Kennedy traveled to Berlin with his delegation in the summer of 1963, he brought a special gift with him: two slide projectors, 2,500 slides, and an accompanying book about American art, all intended for the newly founded Institute for North American Studies at Freie Universität. This kit introducing American ideas is still part of the collections at the institute library to this day – though the projectors are now obsolete. Just a few months after his visit, Freie Universität gave the former U.S. president a posthumous honor: On November 25, 1963, just three days after the attack in Dallas, the Institute for North American Studies was renamed the John F. Kennedy Institut (JFKI).

Kennedy had just been named an honorary member of Freie Universität Berlin in June, delivering a speech in front of the Henry Ford Building that was cheered by faculty and students alike. With such fresh memories, the university shared in mourning the president. His death cast a pall over the start of the 1963 winter semester. Herbert Lüers, at the time the university’s rector, wrote a circular about the events on the occasion of the enrollment celebrations, in it expressing a deep personal sense of loss. Lüers also called the speech the U.S. president had given during his visit in June Kennedy’s legacy for Freie Universität.

At the time, the university had close ties to North America: In the 1950s, shortly after its founding, Freie Universität established its first few partnerships with top American universities, including Stanford, Princeton, and Columbia; plans for an institute of North American studies were already in the works at the time. The founding of the institute was ultimately made possible by the Ford Foundation , which provided about a million dollars intended for various purposes, including to develop the library.

The institute’s founder, Ernst Fraenkel, also had ties with the Americans, which helped him to set the tone. Fraenkel, a German Jew, was able to flee to the United States on the eve of World War II – and he was one of the few scholars to return to Germany in the 1950s. With his work on the American system of government and theories of democracy, he was considered one of Germany’s leading political scientists at the time.

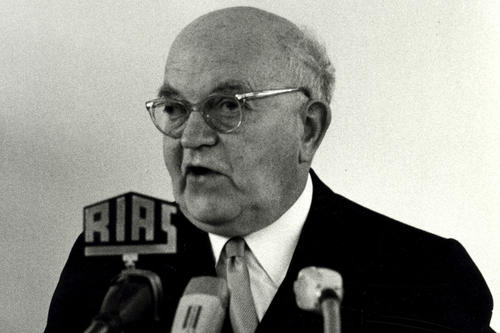

Daring to Try New Things: Institute Founded under Ernst Fraenkel with Help from the U.S.

The founder of the institute, Ernst Fraenkel. A Jewish scholar, Fraenkel managed to flee to the U.S. shortly before World War II. He returned to Germany in the 1950s.

Image Credit: Pollaczek/Universitätsarchiv, Fotosammlung

The institute’s founder, Ernst Fraenkel, also had ties with the Americans, which helped him to set the tone. Fraenkel, a German Jew, was able to flee to the United States on the eve of World War II – and he was one of the few scholars to return to Germany in the 1950s. With his work on the American system of government and theories of democracy, he was considered one of Germany’s leading political scientists at the time.

The institute started out with Fraenkel’s vision: “He wanted to sow the seeds of democracy in the postwar generation,” says Heinz Ickstadt, who enrolled as a student of English and American literature in 1957 and was there for the founding of the institute, under Fraenkel, in 1963. About 20 years later, he would become a professor of literature there himself. Like many alumni, he has vivid memories of turbulent times at the JFKI. Listening to their stories can make one look at the building on Dahlem’s Lansstrasse in a whole new light.

Fifty years after its founding, the institute building has an unassuming, calm outward appearance, with knots of students sitting around in front of the entrance. It is a place where North America is studied and examined from a wide range of different perspectives, encompassing the disciplines of history, culture, literature, political science, sociology, and economics. The Graduate School of North American Studies, which was commended twice in a row in Germany’s Excellence Initiative and receives funding from the German Research Association (DFG), moved in right next door in 2006. More than one-third of doctoral candidates there come from countries other than Germany. For students from the United States, especially, the institute is “the first point of contact,” as Irwin Collier, a professor of economics and the current head of the institute, says.

The difficulties surrounding the institute’s early days have been overcome. There were many reasons things got off to a rough start, including structural ones: While today’s students enroll directly at the institute, with North American Studies as their subject, students originally attended seminars at the institute as part of other study programs. And that meant that in some cases, they did not receive credit for exams because the content was not the same. “For example, you could hardly test history students on the Middle Ages if the subject was called ‘Medieval and Modern History’ at the JFKI,” says Carl-Ludwig Holtfrerich , who started working as a professor of economics at the JFKI and the School of Business and Economics in 1983. Instructors and students, he says, were caught between the institute and their departments.

The JFKI as Part of Global Events: The Student Movement, Strikes and the Cold War

Then, too, global politics left their mark on events in Dahlem. Just a few years after cheering crowds had thronged the streets during Kennedy’s visit, in 1963, the tide had turned. The Vietnam War inflamed anti-American sentiment among the students. They were no longer interested solely in examining and coming to terms with the Nazi era; instead, they developed their own view of current power relations. What started with an outcry over reading lists at the JFKI in 1965 ultimately led to calls for higher education reform. And by the time of Benno Ohnesorg’s death at the hands of the police, during a protest in June 1967, the student movement had swept Freie Universität.

For institute founder Ernst Fraenkel, the development came as a blow. “He demanded respect as an academic authority,” says Ickstadt. “But the students rejected the older generation, whose loyalty to America was still founded on memories of the airlift during the Berlin Blockade.” Fraenkel became disillusioned, even bitter, alumni recall. After his retirement, in 1967, he withdrew completely from university life.

The unrest at the institute lasted into the 1980s. In 1987, during the last major strike, some students even occupied the building over Christmas. “I tried to bar the doors,” recalls Knud Krakau, a professor emeritus of history. “But then the students sat in the cafeteria in the basement for days, playing the strategy game Risk.” All of that took place during the Cold War – and “under the interested, if suspicious, gaze of the Americans,” Ickstadt says.

U.S. envoys feared that the institute was being undercut by Communists, but even a few professors might have been seen as leaning too far to the left. With factionalism and unrest rife, the JFKI was constantly “teetering on the edge” during that era, as Krakau says. At the same time, the protests also had positive consequences, such as their effect on teaching activities: In the wake of the protests of 1968, when students had called for an interdisciplinary approach, lecture series and interdepartmental seminars became part of everyday life, the professor recalls.

The events were also watched closely from East Germany for years: “Sometimes there would suddenly be scholars there from East Berlin who almost certainly paid for the privilege of traveling to the West by having to report on what was going on at the JFKI,” explains Carl-Ludwig Holtfrerich. “One librarian vanished when the Wall came down. And one political scientist who co-supervised the first DFG-financed research training group at the JFKI around the time the Wall came down and was supposed to become a staff member of the institute was discovered to be an informer for the East German secret police.”

The JFKI Today: Excellence in Teaching, Renowned Research, and a Worldwide Network

The JFKI has about 500 students today. The library’s collection has grown from 150,000 to 900,000 media units and offers a range of materials found nowhere else in Europe. Events such as the Ernst Fraenkel Distinguished Lecture Series, which features celebrated scholars such as Paul Krugman, Noam Chomsky, and Frances Fox Piven, have drawn a wide audience, including members of the general public, since 1987.

Ickstadt, Holtfrerich, and Krakau, all of them former heads of the institute, agree: Nowadays, the whole feel of the institute is different. That is something all of them also attribute to their successors. Heinz Ickstadt says that now, in 2013, the JFKI is in the “high phase of its reputation.” This is due in part to the fact that the scholars there maintain excellent networks with colleagues all over the world, as Irwin Collier points out. Freie Universität maintains about 40 official partnerships with higher education institutions in North America. Each year, the graduate school invites up to three visiting professors to come to the university in order to give doctoral candidates a chance to work with prominent experts. For Collier, it is almost as if Ernst Fraenkel’s vision has finally become reality, after 50 years: “The Kennedy spirit probably couldn’t flourish until after the fall of the Berlin Wall,” he says.