Rhetoric of Encouragement

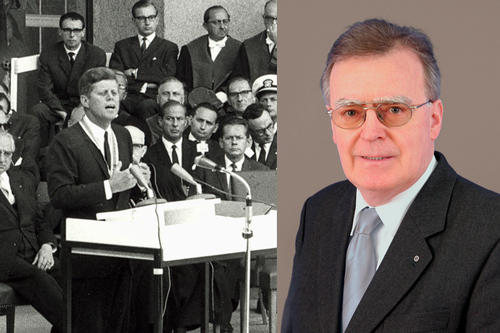

Kennedy’s speech at Freie Universität. An interview with political linguist Josef Klein.

The leader of the Free World at Freie Universität: John F. Kennedy showers his audience with compliments, drawing them in with emotional appeal. wir, the magazine for Freie Universität alumni, spoke with Josef Klein, an expert on political linguistics, about the famous speech. Klein explains how adroitly Kennedy places his messages at the event – and how conventional his rhetoric can be at times.

The leader of the Free World at Freie Universität: John F. Kennedy showers his audience with compliments, drawing them in with emotional appeal. wir, the magazine for Freie Universität alumni, spoke with Josef Klein, an expert on political linguistics, about the famous speech. Klein explains how adroitly Kennedy places his messages at the event – and how conventional his rhetoric can be at times.

wir: Mr. Klein, among Kennedy's many famous quotes, one stands out in this setting in particular: “Ich bin ein Berliner,” which he said in a speech delivered from the balcony of Schöneberg’s city hall in 1963. After that, the President drove to Freie Universität, in Dahlem, where he gave his second speech in Berlin. But even those who were there cannot pick out a single quote from the second speech that had a similarly rousing effect. Why?

Klein: Kennedy’s speechwriters wouldn’t have earned their pay if they had placed a sentence like that in both speeches. A speaker can only place a single core sentence that is quotable and suitable for making headlines on the same day, in the same place. Otherwise, there is a risk that the messages and quotes will cancel each other out.

wir: So which speech was the more important of the two?

Klein: It depends. Kennedy’s speech in Schöneberg was aimed at the masses and the media. It was about sending a signal: America’s president stands by the city on the front lines of the Cold War. He doesn’t say that he is a Berliner solely out of sympathy; he derives this maximum level of identification from the ideal of freedom. He is appealing to emotions; it might be a bit on the cheap side, but it’s very skillfully done, and the crowd loves it.

wir: And in Dahlem?

Klein: The Dahlem speech was aimed at Germany’s leadership. In terms of content, it was far more important than the earlier speech. It boiled down to three messages. First, he told the Soviet Union that the U.S. would support a free West Berlin, even through military means, and he did so in no uncertain terms:“The shield of military commitment will not be lowered or put aside so long as its presence is needed.” Looking at the overall speech, that was just one parenthetical insertion, but it is critically important. After all, the Cuban Missile Crisis had taken place just six months before. This is the only time he mentions the military in the speech.

wir: What are the other messages?

Klein: Second, it is a stern appeal to those in the West who believe that a policy of strength alone will be enough to break the power of the East and bring down the Wall. He urges his audience to face the reality of the situation.

wir: Egon Bahr, at the time the speaker of the Senate under Governing Mayor Willy Brandt, sees this as an indication of the future policy the West will take toward the East.

Klein: Yes, you can definitely see it that way. Especially since Kennedy’s third message is a visionary one. He expresses hope that the conflict between East and West can be overcome, not by force, but by leveraging the full power of freedom and Western values. Granted, he puts it in vague terms, but I was very impressed by that moment, which can be seen as prefiguring the events of 1989.

wir: How does Kennedy convey these messages?

Klein: First he showers his audience with compliments, like he has earlier, in the Schöneberg speech, calling the people of Berlin so strong, so courageous, so free. Then he makes a brief joke referring to Bismarck, and finally he talks about values, raising his voice and becoming more emotional.

"Kennedy doesn’t want to rouse the Dahlem audience like in an election speech.“

wir: How does Kennedy use his voice?

Klein: With great skill. He is very conscious of what he is doing as he directs his audience by raising and lowering both the tone and pitch of his voice. Many political speakers are skilled in the art of winning applause from the audience at the right moments. But Kennedy, with his metallic voice and youthful appearance – next to the professors, military brass, and German politicians, he practically looks like a movie star – is without question a true master.

wir: He speaks about Freie Universität not being “interested in turning out merely corporation lawyers or skilled accountants,” but rather “citizens of the world who are willing to commit their energies to the advancement of a free society.” The quote is now displayed in the foyer at the office of the university management, in Dahlem.

Klein: Yes, he defines the goal of the education imparted not only at Freie Universität, but at all universities. After that, he talks about the ideal image of a professor, and about academic study as an obligation to place oneself at the service of the community’s welfare – not of truth, mind you, but of the community’s welfare. If you will, he first bows down before his audience and then makes rules for them by setting standards. To do so, he cites the example of the U.S. Founding Fathers, a typical point with American presidents, and specifically mentions those who were also scholars themselves: Madison, Jefferson and Franklin.

wir: It is very common to hark back to other great men and women, isn’t it?

Klein: Sure, it’s a common rhetorical tool – and on this point, Kennedy’s speech is a highly conventional university speech, one he also hopes will impress the audience intellectually. He sprinkles it with references to intellectually accepted authorities; even Goethe, of course, gets a mention.

wir: What other rhetorical tools do you notice in the speech?

Klein: He often says things in threes, like when he says West Berlin has been blockaded, threatened, and harassed. Or that even in the face of adversity, Berlin cultivates industry, culture, and academia. Always a set of three, a very common rhetorical device and a highly effective one. He also echoes the trio of truth, justice, and freedom that serves as the guiding principle of Freie Universität, making it part of the second part of his speech. And of course, all of this highlights the contrast with the East, even though that goes unspoken for the most part.

wir: He doesn’t say a single word of criticism.

Klein: Yes, the absence is noticeable. At no time does he talk about Germany’s past, about those who didn’t speak out or looked the other way, or about the complicity of many German intellectuals – and this at a time when the Nazi era was not that long in the past. The Federal Republic is needed right now, as an ally in the Cold War. His many compliments are also meant to take the wind out of the sails of those who are angry about how long it has taken him to act. After all, his visit to Germany, and West Berlin, does not come until two years after the Wall was built.

wir: What kind of image does he project?

Klein: Kennedy doesn’t want to rouse the Dahlem audience like in an election speech. He wants to hit the right points in terms of content and send a message to the people of West Berlin that they should not despair. In all of his public appearances in Berlin, he shows himself to be a true master of the rhetoric of encouragement. It isn’t a single specific rhetorical device that shows this, but rather the way he speaks. In linguistics, we call his style “colloquial”; he talks directly to his audience. He doesn’t speak in a dry, clinical style, like a professor lecturing, but instead draws his listeners in. And he talks about himself often.

wir: Why doesn’t that seem vain?

Klein: At the time, Kennedy can still afford it – his weaknesses and scandals are not yet public knowledge. He embodies the moral authority of the West, protecting West Berlin. And he is natural in referring to himself personally. After all, his entire election campaign was tailored to him as a bringer of hope, a savior. Now, in Berlin, he is making an appearance as a global authority. The strength of his message is associated with him personally.

wir: But not only with him personally?

Klein: No, definitely not. There are a lot of factors that go into how effective a speech is – historical context, the audience’s expectations, the exact time the speech is given. I don’t think the world would still recall Kennedy as an embodiment of hope if he had not been assassinated, because of his responsibility for the Vietnam War, if nothing else.

wir: If Kennedy had come to Berlin before the Wall was built...

Klein: People would probably not have welcomed him so effusively. The situation in Berlin in 1963 was a very specific one. Kennedy’s visit to Freie Universität was a major appearance, but it wasn’t the greatest of his speeches.

About the interviewee

Josef Klein, 72, is an expert on language in politics. A professor of linguistics, Klein combines methods drawn from media studies, the study of speech, and political science for his research. He himself held a seat in the Bundestag for the CDU in the 1970s. After that, he turned his full focus on his academic career, finally going on to serve as president of the University of Koblenz-Landau. Since being granted emeritus status, in 2005, he has been working and teaching at the Otto Suhr Institute at Freie Universität.