Airmail to Jerusalem

Germany and Israel are celebrating 50 years of diplomatic relations this year – but at Freie Universität Berlin, the two countries established ties much earlier.

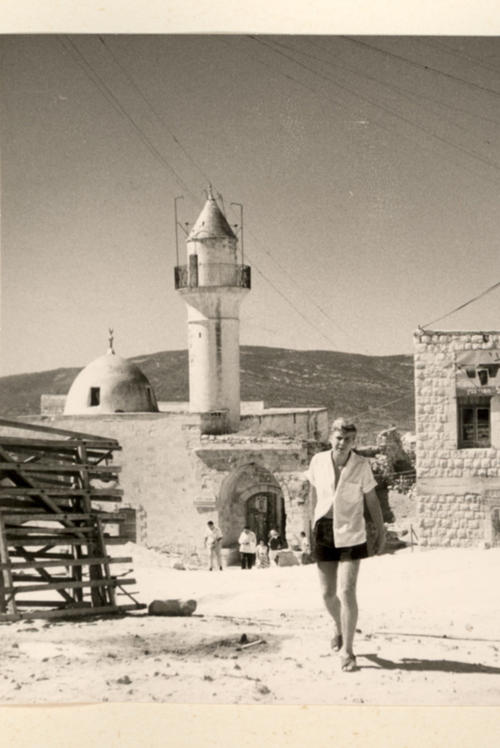

Shlomo Aronson (2nd row, 4th from left), was the first DAAD doctoral fellow from Israel to go to Freie Universität. In 1963, as a journalist, he attended a press conference given by the new German Chancellor Ludwig Erhard.

Image Credit: privat

In August 1957, the president of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem received a letter from students at Freie Universität Berlin. “Your Magnificence,” starts the letter, printed on airmail paper – at the time the usual form of address for university rectors, who still donned a cap and gown and chain of office for festive or formal occasions. The students get right to the point: Their goal, they write, is to “pave the way for academic contact between the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Freie Universität Berlin,” since there has been “a lively interest in Jewish issues” at their institution for years. The students write that lectures and practical courses have made these issues “the subject of extensive scholarly work,” and that there is now also an interest in the state of Israel, and direct exchange and dialogue could make this work “incomparably more fruitful.”

Who were these students, that they wrote a letter like this – just 12 years after World War II, which they had experienced as children or teens? Why did they think their interest in having contacts in Jerusalem might be reciprocated, in light of the persecution of Jews and the Shoah? Official political relations between the two countries were complicated at the time. While the 1952 Reparations Agreement between Israel and West Germany governed German payments of reparations to Israel, diplomatic relations had not yet been established. Diplomatic ties between the countries would not be opened until eight years later, in May 1965.

Enclosed with the students’ letter was another letter, this one from business and economics scholar and then Rector of Freie Universität Professor Andreas Paulsen, making the same suggestion. The letter from the students had been drafted by the “German-Israeli Study Group” (Deutsch-Israelische Studiengruppe), an association founded in 1957 as the first group of its kind in West Germany. It was soon to serve as a role model for offshoots in other German university towns.

The first Institute of Jewish Studies was founded at Freie Universität

Work and travel in the Holy Land: Young Germans and Israelis helped with the apple harvest at the Nahal Oz kibbutz.

Image Credit: privat

The DIS, as the group called itself, organized talks and discussions and published a magazine titled DISkussion, featuring reports from Israel, opinion pieces, and articles protesting against anti-Semitism. As described in the letter, German-Jewish history, the Nazi regime and ideology, and the persecution of Jews were explored in lectures and seminars earlier at Freie Universität than at other universities. The overall environment at the university tended to be more open, likely due in part to the fact that the university administration had made efforts, starting as early as in the 1950s, to invite German emigrants to come to Freie Universität as visiting instructors or appoint them to professorships. Examples include German language and literature scholar Adolf Leschnitzer, political scientist Ernst Fraenkel, and legal scholar Ernst Hirsch.

The first Institute of Jewish Studies in Germany was founded at the university in 1963, as part of an appointment for Jacob Taubes, who had previously taught at Columbia University, in New York. At the time, however, the faculty of Freie Universität also included former members of the Nazi Party, especially within the Department of Law, which would otherwise have been unable to offer any instruction at all, explains Siegward Lönnendonker, who moved to Berlin from Bielefeld in 1958 to study physics. For Lönnendonker, the relative openness with which the very recent past was discussed at Freie Universität was a completely new experience.

In 1963 he became a member of the German-Israeli Study Group at Freie Universität and the editor of DISkussion, which published a report at the time on the first comprehensive seminar, led by Margherita von Brentano and Peter Furth, titled “On the Analysis of Fascist Anti-Semitism.” Still, Lönnendonker says, “Who was or wasn’t Jewish wasn’t an issue for us.” The group took up the common cause, he says, and did not want to stir up difficult memories among Jewish students. “Sometimes, you might learn by chance that someone was Jewish because he was also a member of the Jewish students’ association,” he recalls. In 1963, Lönnendonker traveled to Israel on a trip organized by the German Federal Association of German-Israeli Study Groups (Bundesverband der Deutsch-Israelischen Studiengruppen).

Young Israelis and young Germans meet

The photo at left shows student Siegward Lönnendonker (front) on a break from picking cotton.

Image Credit: privat

The impressions he formed during his two-month stay in Israel are still quite vivid today. On arriving at the airport in the “Holy Land,” Lönnendonker recalls, he was overcome by “chills,” and he thought: We can’t let our feelings overwhelm us now. He pitched in during the apple and cotton harvest at the Nahal Oz kibbutz, near Gaza City. He was impressed by the young Israelis: “very self-confident men and women.” And he, the son of a Nazi true believer, met concentration camp survivors for the first time. “They asked us first how old we were. My birth year, 1939, was all right. And then they showed the numbers tattooed on their arms.”

That must have been difficult. But how much more so was the contact between Israelis and Germans in the perpetrators’ own country? Shlomo Aronson was the first Israeli doctoral candidate to come to Freie Universität Berlin on a scholarship from the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), which he did in 1962. He earned his doctorate with a dissertation on Reinhard Heydrich and the origins of the German security service and the Gestapo. A short while before that, Aronson, who also worked as a journalist, including for Israeli radio, had reported on the Eichmann trial, and as part of these activities, he had heard a rumor that Heydrich – the head of the Wannsee Conference and a principal architect of the Holocaust – had Jewish roots.

Now Aronson wanted to find out whether this was true (it was not), and so he traveled to Germany. For his project, he interviewed SS members who had worked with Heydrich, along with members of Heydrich’s family. The research wasn’t always easy. “My poor wife,” Aronson recalls. “Once, when the phone rang, she picked it up and blanched as she passed me the receiver. ‘Ms. Heydrich wants to talk to you,’ she said. It was a niece of Reinhard Heydrich, who lived not far away from the Aronsons’ apartment in Berlin. Aronson met with her later for an interview.

Many Israeli scholars and scientists had experienced persecution and displacement themselves

Siegward Lönnendonker traveled to Israel in 1963 with a German-Israeli study group. The photo above was taken on a tour of the country.

Image Credit: privat

Talking to the perpetrators and their family members was very difficult for Aronson, especially because his family had been personally affected by the Shoah. Aronson, who was born in Tel Aviv in 1936, had chosen his topic as a way of better understanding his mother’s history. His mother, who was from Poland, learned from refugees in 1943 that her entire family – 80 people in all – had been deported. The news came as such a severe blow that she lost the will to live, Aronson recalls. “Although she had survived, she stopped being a wife and mother,” he says.

Although the family lived in Palestine at the time, under what was then the British Mandate, Aronson says he still lost his mother to the Holocaust. Many Israeli scholars and scientists had in fact experienced persecution and displacement themselves, and they knew of the magnitude of the Holocaust from family stories. As a result, Israeli academics were sharply divided on the question of whether they should cooperate with their German counterparts, says Jürgen Renn, Director of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin.

Together with Hanoch Gutfreund, a former president of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Renn has studied the history of the scholarly and scientific contacts between the two countries. Their colleagues in Germany, on the other hand, often “still indulged in the notion that it was only a few Nazis who had committed crimes in the name of the German people,” Renn says. The process of coming to terms with the history of their own specific disciplines did not set in until fairly late, especially in the natural sciences – in the 1980s. Paradoxically, political motivations were initially the strongest factors pushing people to make contact at the academic and scientific level. Later, in the 1970s, it was academia that set the pace for understanding.

The long road to reconciliation

The idea that scientific, “objective representation” in particular could “pave the way for reconciliation” was advanced by the university management of Freie Universität when, in the early 1950s, it wrote to Adolf Leschnitzer, a scholar of German language and literature who had emigrated to the United States, to invite him to Berlin as a visiting instructor. It also underlay the letter that Rector Paulsen sent to Jerusalem in 1957, together with the letter from the students.

There was greater skepticism on the Israeli side. In September of that year, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem confirmed receipt and promised to respond. But, Gutfreund reports, the question was not discussed by the university administration until December 1958 – a year and a half later – and the ultimate decision was negative. The only evidence of this is found in the minutes of the university administration’s meetings, however; no response letter to Freie Universität has been found so far.

Today, nearly 60 years after the letter and after the first delegation of German scholars and scientists – a group from the Max Planck Society, led by Otto Hahn – visited Israel, in 1959, Freie Universität Berlin and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem are connected by a strategic partnership. Their cooperative relationship encompasses research, teaching, and administrative activities. In one project, for example, students from both countries who are enrolled in teaching credential programs discuss how the Holocaust is treated as a subject in school textbooks, visit important remembrance sites together, and talk about their own family histories.

“German-Israeli scientific and academic cooperation is a success story”

What started out more than 50 years ago with a letter from Berlin has now developed into an extensive relationship of friendship and cooperation between two universities, in spite of a difficult and bumpy start. Doctoral candidates will soon also be able to earn a joint doctorate from both universities, with two supervisors, in Jerusalem and Berlin. “The history of German-Israeli scientific and academic cooperation is a success story,” Gutfreund says with conviction.

Last Tuesday, when the presidents of the Hebrew University and Freie Universität, Menahem Ben-Sasson and Peter-André Alt, respectively, signed an agreement establishing joint doctoral programs, Gutfreund felt that the event also marked the close of a chapter in German-Israeli history that had remained incomplete: “It was as if the letter sent by airmail from Berlin was receiving a response, 57 years later.”

The original letter from the rector of Freie Universität and the group of students is in the archives of Freie Universität Berlin (University Archives, Call Number: Abt. IV Außenamt.)

Anniversary Year

Programs, Workshops, Conferences

This year, Israel and Germany are celebrating 50 years of diplomatic relations. Freie Universität Berlin is hosting a variety of conferences and workshops for scholars and scientists in cooperation with the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and other Israeli universities. A lecture series on the history of German literature from the Middle Ages to the present has been running in Jerusalem since the spring/summer semester and will be concluded with a final event in April 2015. A teaching project for education students majoring in history and ethics at Freie Universität Berlin and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem has been running simultaneously in Berlin and Jerusalem. Students attend seminars at the same time, then exchange ideas and impressions over the Internet, and work together to jointly develop teaching materials on the Holocaust. The German-Israeli Research Training Group “Human Rights under Pressure – Ethics, Law, and Politics” is expected to be officially opened in June 2015. It is funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the Einstein Foundation Berlin. Each year 20 doctoral students from each university will be educated within the Training Group.

Further Information

This text originally appeared in German on February 14, 2015 in the Tagesspiegel newspaper supplement published by Freie Universität.