Letting People Speak

Annette Gerstenberg, a professor of French and Italian linguistics, studies language in advanced age.

Sep 07, 2015

How does language change over a lifetime, and how does it change between different generations? Annette Gerstenberg studied this question in France.

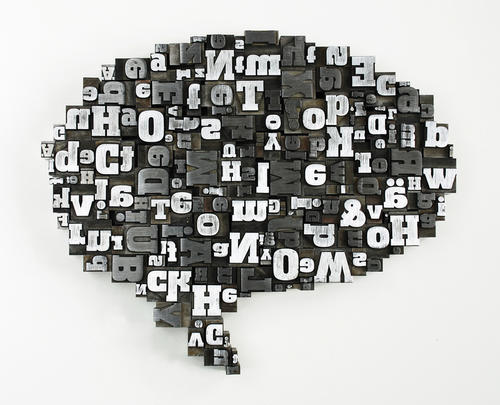

Image Credit: misterQM/photocase.com www.photocase.de/foto/196891-stock-photo-informationstechnologie-technik-technologie-sprechen-kunst-denken-kultur

The interviewees that linguist Annette Gerstenberg visited for her study in France told about their lives. Most of them were between 70 and 94 years old.

Image Credit: Annette Gerstenberg

This photo from 1944 shows a scene from when Orléans was liberated from German occupying forces by the U.S. Army. The study participant provided it to Annette Gerstenberg.

Image Credit: privat

Annette Gerstenberg is a professor of linguistics at the Institute of Romance Languages and Literatures at Freie Universität.

Image Credit: Tobias Mayer

When it comes to studying the language of specific age groups, most scholars focus on the language used by young people. Annette Gerstenberg, a scholar of Romance linguistics at Freie Universität Berlin, is dedicated to a different generation: She studies language in advanced age.

It might have been the internship she did at a nursing home in Florence after graduating from high school that first sparked Annette Gerstenberg’s interest in the language of the elderly. But that interest certainly grew when she saw the lack of knowledge that existed in this field. “In Romance languages and literatures in particular, the number of research works on this topic was very modest,” says Gerstenberg, who focuses on Italian and French. “When I was writing my professorial thesis, it was important to me to work in a field that had not yet been researched thoroughly,” she adds.

In the specialized literature, she found numerous instances of the “deficit hypothesis” when it came to the language of the elderly. “Language development over a human lifetime was described as being like an upside-down U, with the high point coming in mid-life and language deteriorating with advancing age,” she explains.

“There is no typical language of the elderly.”

Gerstenberg did not assume, though, that the language used by older people shows pathological processes in particular. “I don’t use terms like ‘language of the elderly,’” says Gerstenberg, who is 41. In her experience, there is no typical language of the elderly, since a person’s specific generation determines certain factors that dominate that person’s language use, and each generation brings different typical speech patterns with it, which in turn also adapt to how language is used in the wider society.

Gerstenberg started the empirical part of her professorial thesis in 2005. She traveled to Orléans, where she spent several weeks interviewing 56 older people. Forty-eight of them were between the ages of 70 and 94.

There were good reasons to choose Orléans specifically. First, the language of the local area, not far from Paris, is standard French, so dialects would not be much of a distraction. Second, Gerstenberg would be able to build on what linguists call a corpus: A group of teachers of French from England had started collecting and documenting recordings of speech across all generations in the area back in 1968. The resulting body of knowledge, called the Orléans Corpus, also marked the start of cooperation within a local working group of linguists. Gerstenberg is an associate member of the group today.

After meeting Gerstenberg in person, it is not hard to see why people open up to her quickly, or that she is a good listener. Although there is no trace of her home region, the Rhineland, in her speech in German, the scholar does display typical Rhineland manners around speaking to others. As she herself says, “One part of it is that as a Düsseldorf native, you talk to people in the elevator even if you don’t have to.”

Talking to Others and Listening Closely

She found interviewees for her research in France at nursing homes through friends – or she simply approached people on the street. Gerstenberg wanted to create a situation that was as similar as possible for each interview. Participants were to be allowed to develop their own flow of speech, so the linguist adopted a strategy of active listening. The older people spent about 45 minutes each talking about their lives. They knew that the interviews were being conducted under a university research project, and that they were part of an oral history project.

Gerstenberg published her professorial thesis, titled Generation und Sprachprofile im höheren Lebensalter (Generation and Language Profiles in Advanced Age) in 2011. The work included the results of her research in Orléans. The term “generation” plays a central role in the thesis. Many of those interviewed attached great value to their schooling. “For these children of the French Third Republic, schooling is viewed as the path to social advancement,” Gerstenberg says. “To them, getting an education means education in language, so many of the interviewees were very careful in their choice of words and how they formed sentences.”

“Talking is an effort.”

Gerstenberg went back to Orléans in 2012 to meet with her former interviewees. She was able to find 34 of the original 56. The setting was the same, but in her analysis, Gerstenberg concentrated on small units taken from the interviews conducted seven years before, on anecdotes and certain recollections, most of which were spontaneously retold in the same way. In some cases, Gerstenberg deliberately prompted subjects to repeat their stories and then compared the two versions. Which strategies were used to tell stories? How had they changed during later telling?

The narrative units had grown shorter, and pauses were longer. “Talking is an effort,” Gerstenberg confirms. “You can see that from these kinds of changes.” Another factor involved in this was that the older people used fewer fill words, which cost additional energy to produce, when speaking in 2012. The percentage of words that were used very frequently had declined overall. She says there is an astonishing degree of stability when it comes to the core of a story – the most important information. This extends to things like recounting speech verbatim.

“Younger people are less organized when telling stories, with more jumps.”

As another step, the scholar conducted an experiment in “narrative priming.” She exposed the students she was teaching as part of a guest instructor position at the University of Orléans to the older people’s stories. Then she prompted the younger people to start talking, asking about anecdotes from their own childhoods. After that, the linguist compared the two groups’ narrative styles and strategies.

“An increase in pragmatic competence is clearly apparent in the older group,” Gerstenberg says. “Their narratives are better organized, composed like written texts, with an introduction, a high point, and an evaluation, while the younger people tell their stories in briefer terms and tend not to use elements that lend them structure.”

Gerstenberg was appointed to a position as a professor of linguistics at the Institute of Romance Languages and Literatures at Freie Universität Berlin in 2013. Can she still converse freely with others when she goes out at night, or does she always pay attention to speech patterns? “Yes, I do pay attention to those,” she says. “But I wouldn’t want it any other way. Language simply interests me too much for that. I have always been fascinated by language – in any form.”

Further Information

Further Reading

Language Development: The Lifespan Perspective (John Benjamins Publishing Company) was published by Annette Gerstenberg and Anja Voeste in July 2015. This volume is a collection of essays on German, English, French, and Italian. It is devoted to the development of language in mid-life and in advanced age and the possibility of exploring this subject via longitudinal studies. The researchers used different types of sources for this, including collections of letters, autobiographies, literary texts, and audio archives.

Contact

Prof. Dr. Annette Gerstenberg, Tel.: +49 30 838 60789, Email: annette.gerstenberg at fu-berlin.de