Syrian History in Shards

In a painstaking excavation, archaeologists have reconstructed how people in present-day Syria once lived

May 07, 2014

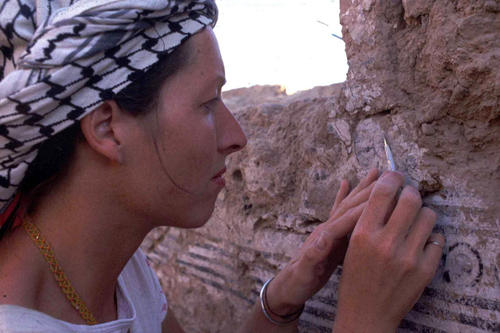

A restorer prepares preserved remains of wall paintings in the Red House, the heart of the dig.

Image Credit: Projekt Tell Schech Hamad

Scholars from Freie Universität have been working for decades on excavating the native remains of the Assyrian city of Dur-Katlimmu.

Image Credit: Projekt Tell Schech Hamad

In the 2nd century BCE, the dead were buried in “double-pot” graves.

Image Credit: Projekt Tell Schech Hamad

A chance find in a child’s hands, decades of excavation work, thousands of artifacts – and, finally, the civil war. After about 35 years, archaeologist Hartmut Kühne’s research project at the Tell Sheikh Hamad site in Syria will draw to a close this year. He and his team have reconstructed how people in the area lived 3,000 years ago, down to the smallest details. How severely the war has affected the excavation site in the meantime is still completely uncertain.

It all started out in 1977, with a group of playing children. German scholars on an expedition in Syria discovered that the children were holding fragments of clay tablets containing inscriptions. The scholars had actually traveled to the site with a different aim: to collect archaeological data on the settled hills along the Khabur River for a historical map being compiled by the University of Tübingen.

“We asked them to take us to where the artifacts had been found,” recalls archaeologist Hartmut Kühne, more than 35 years later. Kühne, who was 34 at the time, has been a professor of Near Eastern archaeology at Freie Universität since 1980. “The farmers had just put in a new irrigation channel, and it had brought intact inscribed clay tablets and tablet fragments to the surface.”

Closer investigation revealed an incredible find: evidence of the provincial capital of Dur-Katlimmu, from the Assyrian period, whose exact location and extent had been a complete mystery to scholars until then. “Assyria was the very first world power, dominating all of the other states of the time,” Kühne explains. The empire grew from 1350 BCE onward, reigning at the height of its power for about 140 years after 750 BCE Then, in 612 BCE, the empire collapsed, and the Babylonian Empire became the leading political force.

Excavation Started in 1977

Kühne has dedicated himself to this place in the Syrian steppe to this day, with support from the German Research Foundation (DFG) from 1978 onward. The goal was to take Dur-Katlimmu as a model for analyzing the urban structures of Assyrian provincial capital cities. The DFG’s support expired in December 2013, after 35 years.

Since the start of the war in Syria, the scholars have been focusing primarily on analyzing journals of the excavation and publishing their findings – a dozen volumes have already been published, and another seven are scheduled to follow. They plan to use items placed in reserve to continue their work up until the end of 2014, examining crates full of shards and working with artifacts. The artifacts are linked with their specific find sites by computer to allow for studies of the objects’ functions and uses.

The heart of the dig is the “Red House.” This excavation area alone is a big larger than a football field. “We assume it was the residence of a high official of the king who bore the title of ‘Confidant,’” explains Kühne.

The foundations and objects that have been excavated bring the past era to life: Researchers know where baths, offices, and public and private rooms were located, and they can describe everyday life in the various parts of the site. Hundreds of thousands of ceramic potsherds were found here alone, and Kühne’s colleague Janoscha Kreppner has analyzed more than 50,000 of them.

Civil War Halts Excavation Work on the Site

Alongside ceramic pots the size of buckets, which were used to store food, people at the time used plates, drinking bowls, and bottles with metal tubes to go with them, through which they sucked out the contents – forerunners of modern straws. The excavations also give scholars insight into changes in regional vegetation, the diet people ate at the time and their living circumstances.

Kühne’s original goal was to make the fruits of the decades of work performed at Tell Sheikh Hamad accessible to people from the area and tourists starting in 2008. The north wing of the Red House was rehabilitated. A visitor center and an archaeological park were planned. But 2010 would turn out to be Kühne’s last stay at the site, at least for now.

Since the Syrian civil war broke out, returning to the site has been out of the question. “I have no way of knowing how bad the damage is,” Kühne says. “I hope this disastrous civil war will be over soon, and that Syria’s rich world cultural heritage survives it,” he adds.

Further Information

- Prof. Dr. Hartmut Kühne, Institute for Ancient Near Eastern Archaeology, Freie Universität Berlin, Tel.: +49 30 83 85 20 12, Email: hartmut.kuehne@fu-berlin.de, www.schechhamad.de

A longer version of this article was published in German in the Tagesspiegel supplement issued by Freie Universität.