Documenting Horror

80 years after brutal repression, a multimedia portal documents the fate of trade unions under the Nazi regime

May 06, 2013

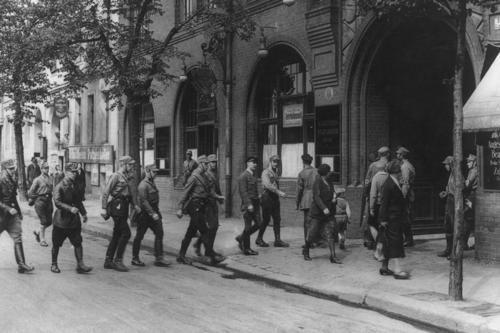

Members of the paramilitary Nazi Sturmabteilung (SA) stormed all of the union halls – marking the start of full forcible coordination of all aspects of German society by the Nazis.

Image Credit: ullstein bild

As late as May 1, 1933, the Day of Labor holiday, the Nazis had feigned agreement with the trade unionists. The very next day, members of the paramilitary Nazi Sturmabteilung (SA) stormed all of the union halls – marking the start of full forcible coordination of all aspects of German society by the Nazis. Many former functionaries were interned at concentration camps such as the SA prison at Papestrasse (now Werner-Voss-Damm 54 a), not far from the Südkreuz S-Bahn station.

More than 2,000 people were kept prisoner and tortured in the cellars there. Information on what happened there is now available online. The multimedia portal includes an audio clip with recollections from union secretary Ludwig Küchel. He reports on how he was herded together with hundreds of other “anti-Fascists,” and how blood and hair were smeared on the walls and screams were heard constantly. Like the other prisoners, Küchel had to kneel on the cement floor for hours. Every night, prison wardens beat them with rubber cudgels.

Eightieth Anniversary of Nazi Crushing of Trade Unions

“Many trade unionists fell victim to the Nazis, but that still isn’t widely known,” says Professor Martin Lücke of the Friedrich Meinecke Institute at Freie Universität Berlin, who developed the multimedia portal with students as part of a seminar. The portal went live in late March. The date was no accident: May 2, 2013, marks the 80th anniversary of the crushing of the trade unions, which started with the storming of the union halls and the murder of numerous union functionaries. With this in mind, the German Confederation of Trade Unions (DGB) commissioned Freie Universität Berlin to carry out the project. “We think it is wonderful that young people who are themselves still in the learning process developed it,” says Dieter Pougin of the DGB. “We are very happy with the result.”

Unions Were Important Cultural Link

The centerpiece of the website is a map dotted with blue flags. More than 50 locations in Berlin are marked this way. They include the horseshoe-shaped Hufeisensiedlung housing development planned by Bauhaus architects Bruno Taut and Martin Wagner in the south of Neukölln – one of the first large-scale housing developments of the Weimar era. The construction work was made possible by trade unions.

The development thus also offers proof of the cultural diversity that was destroyed forever when the unions were crushed. “At the time, the unions were a cultural link within society,” says Lücke. “For example, they were involved in a lot of residential construction activities, and it was not unusual for them to build very innovative architecture.” No wonder the Hufeisensiedlung was named a World Cultural Heritage site by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 2008.

Shoulder to shoulder, bundled up in thick coats, people stood together during the official dedication as a photographer took their picture. This snapshot from the archives of the Academy of Arts is also featured on the online portal. Users can also take a look at a typical worker’s kitchen and stroll through the various streets of the historic housing site.

An aerial photo shows that back in 1930/31, fallow land started just a few streets past the development. “New media has made history even more accessible,” Pougin says. With this in mind, other cities are also interested in an online portal like the one Freie Universität Berlin has created. “There will be a similar portal in Duisburg soon, for example,” he says.

To find all of the photos, letters, and audio clips, students had to sift through the archives themselves. “At times it got really adventurous,” recalls Stefanie Kosmalski, who was one of the five students forming the core of the team. “We got one of the photos via a roundabout path from an archive in Moscow.” It was also difficult to find sources on female trade unionists. “There were hardly any women in the top ranks,” Lücke says, “but they played a major role in the cultural life of the unions,” for example, in sports.

Day on Fichteplatz

Over just a few years, the Fichte Athletic Association (Turnverein Fichte) grew to become the largest workers’ athletic association in Germany. Shortly before the Nazis disbanded it, the association had more than 8,400 active members, who played soccer and tennis, swam, and practiced track and field disciplines. The members definitely enjoyed these activities, as portal users can learn in a five-minute audio clip. They follow along with unionist Otto Giese on a “day on Fichteplatz.” Workers “really dug in” to a meal of bread with spreads and sandwich toppings for breakfast and soda. Children enjoyed playing ball, and men sunbathed shirtless. Songs were sung and some played the tambourine or mandolin. The nice thing about it, Giese recalls, was “being able to move around in a casual and relaxed setting.”

Moving Farewell Letter

The multimedia portal offers an up-close look at people and how they lived back then. For example, it features Wilhelm Leuschner, arguably the best known of Berlin’s unionists. “He is the hero of the trade unions,” says historian Lücke. A member of a plot to assassinate Hitler, Leuschner was executed by the Nazis in 1944. The website shows Leuschner’s farewell letter to his son:

“My dearest Wilhelm,

Farewell. Stick together. Rebuild everything. Give my best wishes to Leni and Beate and the little grandchild to come. Take care of mother. Best wishes to all friends and acquaintances.

All the best, with love,

Papa.”