In Search of Lost Art

Provenance researcher Meike Hoffmann works with experts and students to reconstruct the art collection, broken apart during the Nazi era, of Berlin-based publisher and patron of the arts Rudolf Mosse.

Apr 21, 2017

The Mosse Family Banquet, a painting by Anton von Werner, was five meters wide and took up an entire wall of the Mosse-Palais. It has disappeared; the smaller oil sketch was restored to its former owner and now hangs in the Jewish Museum in Berlin.

Image Credit: Jens Ziehe (purchased using funds from Stiftung Deutsche Klassenlotterie Berlin)

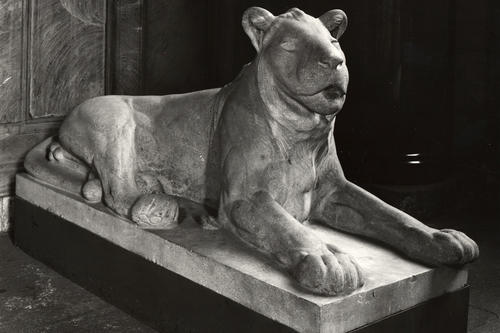

The stone lion by August Gaul (1903) was also returned.

Image Credit: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

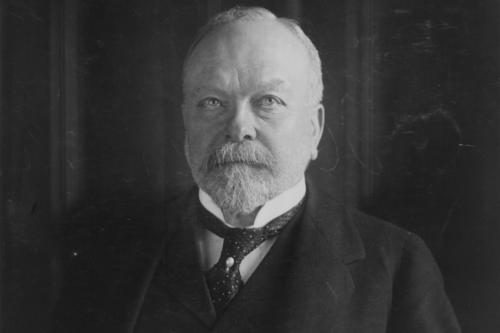

A media czar in Imperial Germany and the Weimar Republic: Rudolf Mosse, 1843–1920.

Image Credit: picture-alliance/akg-images

In 1903 Mosse moved into the publishing building on Jerusalemer St., designed by architects Cremer &Wolffenstein (later redesigned by Erich Mendelsohn). Destroyed in World War II, rebuilt after 1990, it opened as the Mosse-Zentrum in the mid-1990s.

Image Credit: Bernd Wannenmacher

It sounds like detective work on a grand scale: How does one find several thousand works of art that vanished 73 years ago? How does a person go about searching for the collection that the Nazis stole from the heirs of one of the most influential men in Imperial Germany and the early Weimar Republic, publisher and patron of the arts Rudolf Mosse? Some pieces were sold off in forced auctions, some were bought in private sales, and the rest were scattered to the four winds. How do you find the proverbial needle in a haystack, not just once, but thousands of times over?

Meike Hoffmann, an art historian with a doctorate who works at the “Degenerate Art” Research Center at Freie Universität, is right at home researching provenance. Studying expropriated art and reconstructing the paths that a work has taken since it was seized by the Nazis is her day-to-day business. Normally, provenance researchers in Germany are commissioned to review the origins of works from collections in museums or privately held collections. That was the case a few years back, with Cornelius Gurlitt – the son of Hildebrand Gurlitt, an art dealer active during the Nazi period – whose collection appeared in Munich in 2012. Hoffmann was a part of the research right from the start.

This time, in the Mosse case, the situation is different. The works that are supposed to be investigated have disappeared – just as was initially the case in the research done on art that was classified as “degenerate” and banned from museums in 1937. This means the Mosse collection first has to be reconstructed before the winding paths the works took to reach their current locations can be traced in the first place.

To tackle this huge task, a research project was recently launched at the Art History Department at Freie Universität, with Hoffmann as coordinator: MARI – the Mosse Art Research Initiative. This cooperative initiative between Freie Universität and the heirs of Rudolf Mosse, who live in the United States, is the first public-private partnership of its kind in the field of provenance research. The project is funded by the German Lost Art Foundation and the heirs, with both sides contributing just under half a million euros in total to support the project over a two-year period. Further cooperation partners include the Kulturstiftung der Länder, the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation, the Mathildenhöhe in Darmstadt, the Kunsthalle in Karlsruhe, and other museums. MARI is being called a model project for this reason. It is also a stroke of luck: While museums and heirs – or their attorneys – are often on opposite sides of the issue, everyone here will be pulling together in the same direction.

Rudolf Mosse’s art collection was one of the largest private collections of its time. Mosse, who published the legendary bourgeois liberal Berliner Tageblatt and many other newspapers and magazines, enjoyed a meteoric career. After apprenticing as a bookseller, he went into business for himself as an advertising agent, and in just a few years had built up a mighty corporate empire. The five-story printing and publishing building on Jerusalemer Straße at Schützenstraße, in Berlin’s Mitte district, was – and remains – solid physical proof of his success. Around 1900, Mosse was one of Berlin’s most important figures and one of the three richest men in the city. A patron of the arts, he supported charitable institutions. He and his wife founded the Emilie-Rudolf-Mosse-Stiftung, which built a youth center for 100 children in Wilmersdorf, he donated to the Berliner Asylverein für Obdachlose, which worked with the homeless, he was involved in the reform Jewish community, he supported artists – and he acquired art.

The family lived on Leipziger Platz, where the patriarch of the family had had a villa dubbed the “Mosse Palais” built in the early 1880s. The many pieces Mosse had collected as an art lover were used to decorate his country estate, Schloss Schenkendorf, in Brandenburg, and the palatial villa in Berlin, which he also opened to visitors. Sculptures, statues, paintings and tapestries, artisan crafts and porcelain, furniture and textiles, Egyptian antiquities, Benin bronzes, and East Asian pieces were all displayed over three stories and in 20 rooms, along with valuable manuscripts and rare books. In all, there were about 4,000 works from unknown and famed artists alike, including Adolph Menzel, Wilhelm Leibl, and Anselm Feuerbach.

Mosse died in 1920, followed four years later by his wife. The estate was inherited by the couple’s adopted daughter, Felicia. She and her husband, Hans Lachmann-Mosse, and their three children were forced to flee the Nazis in 1933, traveling first to Switzerland and then to the United States via France. Lachmann-Mosse had continued to manage the family empire after his father-in-law’s death. The company, which was hard hit by the global economic crisis, was ultimately liquidated by the Nazis. The possessions the family had left behind, including the art collection, were placed in trust by the Reich authorities themselves and then auctioned off.

This is where MARI comes in. The most important sources for reconstructing the collection so far have been the collection catalogs. One of them, dated to 1908, was published by Rudolf Mosse himself, while later ones were published by Hans Lachmann-Mosse. There are also auction catalogs that are still preserved. In May and June 1934, furnishings and parts of the art collection were auctioned off at the Mosse-Palais and at the home on Maßenstraße where the Lachmann-Mosses had lived. The community of heirs has entered the objects listed in the catalogs in the digital lost art database, which now includes about 1,000 works from the collection. Other sources include records, journals, and correspondence between the publisher and artists. One rich trove is Mosse’s own Berliner Tageblatt, which published regular reports on academy exhibitions in Berlin and Munich and acquisitions of works of art.

Hoffmann is being assisted in identifying and reconstructing the collection by three research associates. She also offers undergraduate and graduate seminars focusing on the Mosse project specifically. In these courses, students use specific examples to learn the craft of provenance research and gain the skills they need for potential future employment in this field. This past winter semester, for example, the students were assigned to identify paintings by unknown artists of the 19th century that were listed in the auction and collection catalogs.

Their first task was to find out something about the respective painter: Is there a monograph? Are there exhibition catalogs from then and now? Have experts ever published anything about him or her? After that, they moved on to the archives. The Central Archive contains all of the files of Berlin’s State Museums, and the State Archive contains the Commercial Register, where sales in the art trade can be researched. Records kept by the Reichskammer der bildenden Künste (Reich Chamber of Fine Arts) can also offer insight, since art dealers were required to register with the chamber, as can construction and reparation files. Using this approach, the students were able to positively identify several of the paintings that had previously been entirely unknown, and even located two of them. Now the seminar results need to be reviewed by the professional researchers involved in the Mosse project, who are also responsible for tracing how the works were lost and where they went.

Roger Strauch, a step-great-grandson of Rudolf Mosse, views MARI as offering an example of “Germany building bridges instead of walls.” Strauch, who is from California and traveled to Berlin for the official start of the research project, represents the community of heirs. His goal is to keep the memory of his great-grandfather and his social activities alive: “Rudolf Mosse was as prominent and powerful in his day as Bill Gates or Mark Zuckerberg are today,” says Strauch. But the matter also concerns “the truth, and the consequences that result from it”: Stolen items would need to be restored. The Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation, which actively examines its museums’ collections for looted and stolen art, has already tracked down nine works and returned them to the family; it was able to buy back two of them.

Provenance research opens a door to a dark chapter in German history, especially for young people, says Hoffmann when she is asked why her students show so much interest in the subject. “This is an area of Nazi history that we can still help to clear up today. Not just in terms of posterity, but in concrete terms for the descendants of those persecuted by the Nazis,” she explains. Strauch, for his part, hopes the works will be shown in an exhibition someday after they have been found. He says his family has a fundamental interest in making the collection accessible to the public – something Rudolf Mosse would surely have approved.

Further Information

Dr. Meike Hoffmann, Freie Universität Berlin, Department of Art History, “Degenerate Art” Research Center, Tel.: +49 30 838 70338, Email: meikeh@zedat.fu-berlin.de