A Bookshelf for Data

In the Edition Topoi, research data can be published for long-term accessability.

Jun 28, 2016

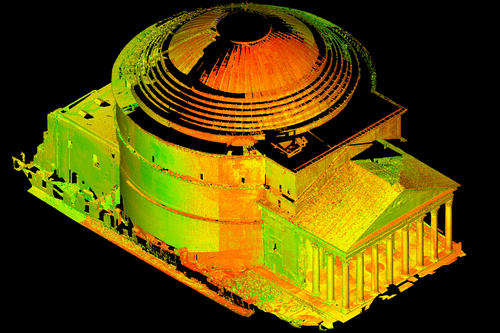

The Pantheon in Rome in a digital collection of the publication platform "Edition Topoi."

Image Credit: The Bern Digital Pantheon Project. (2016). Isometric projection, facing south-west. Edition Topoi. doi.org/10.17171/1-4-83-1

Libraries – like here, the Philological Library of Freie Universität Berlin – are not becoming obsolete even in the digital age.

Image Credit: Bernd Wannenmacher

Citing a book or essay is part of scholarly work. But what about images, collections of sources, digitized objects, 3D models, or databases, especially if they are only present in virtual form on the Internet? These kinds of research data are playing an increasingly important role in the field of studies of ancient civilizations.

However, it is still all too seldom the case that they are made directly accessible when a book or article is published, says Gerd Grasshoff, one of the two directors of the Topoi Excellence Cluster, a research alliance between Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

Grasshoff says this was the impetus for creating a publication platform that offers access not only to “traditional” scholarly works, like monographs and essay collections, but also research data: the Topoi Edition.

With the Edition Topoi, the cluster has committed itself to the idea of open access. All publications – books, periodicals, data – are made available worldwide. This is important since Topoi is a research alliance whose scholars work together with colleagues in Eastern Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East – meaning in countries where budgets for subject-specific literature at libraries and academic institutions can be slim.

The researchers also engage in archaeological excavations in crisis regions. “Whenever the Internet is stable, our colleagues outside Berlin can also read the publications. This leads to democratization of the academic landscape,” says Michael Meyer, the other director of the excellence cluster, who is a professor of prehistoric archaeology at Freie Universität Berlin.

The Edition Topoi sets high standards of quality for books and data publications alike: Both forms of publication are managed editorially and will be available on the Internet on a long-term basis. Furthermore, the editors developed a new format for the publication of data called a “citable.”

“A book has a title, an author, and other pieces of information that make that book unique,” says Grasshoff, who is a professor of history of science of classical antiquity at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. In a similar fashion, research data can now be published as a “complex unit” in a form that is suitable for citation so that they can always be found in the future and, even more importantly, so that readers can work with them.

This is no easy task, as programs have been changing since the start of scholarly work with computers, and files become incompatible with newer systems and formats. This is one way they differ from manuscripts, books, and index card collections, which can still be read even after centuries. The citable can be downloaded as a text file, making it readable for computer users, regardless of the program or operating system.

Digital collections of, e.g., cylinder seals and Babylonian astronomy records are accessible as citables in the Edition Topoi. The collections of Topoi cooperation partners, such as the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities, the German Archaeological Institute, the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, and the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation, can also be integrated. In this way, scholars and researchers from other institutions can not only review a publication from scratch, but can also continue to work with the data themselves or even correct or add to them.

Grasshoff firmly believes that research data will become increasingly important in the future in terms of impact, meaning how a publication affects the further development of the field. As he points out, this kind of sharing of knowledge is already widespread in the natural sciences, but has not yet caught on the same way in the humanities and cultural studies.

At the same time, the idea of collecting research data is not a new one. “Research data have been collected systematically in the field of studies of ancient civilizations in Berlin for 200 years,” Grasshoff says. Long before 3D modeling was invented, coins were pressed into sealing wax to take impressions. In the “epigraphic squeeze” method, casts of ancient grave inscriptions were made using soft paper dampened with water.

The Edition Topoi is now continuing this physical method of securing research data on the digital level. Doesn’t that mean digital publication platforms like the Topoi Edition will make libraries obsolete at some point?

“On the contrary; libraries are the foundation for the Topoi Edition,” Grasshoff says. The university libraries of Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin ensure the ongoing availability of books and of the digital collections of research data known as repositories. And printed books will also not disappear, Michael Meyer says.

All books published as part of the edition are therefore available as books on demand, with an appealing layout and reader-friendly paper. The two Topoi directors – and many other scholars besides – still view books as a wonderful way to receive the work of their colleagues. Or, as Grasshoff puts it, “Printed books are a good knowledge interface for people.”