Writers on the Big Screen

Literary and media scholar Stefan Keppler-Tasaki studies how authors used early film.

Dec 15, 2016

Early media heroes: physicist Albert Einstein and author Thomas Mann in exile in Princeton, New Jersey, in 1938.

Image Credit: akg-images

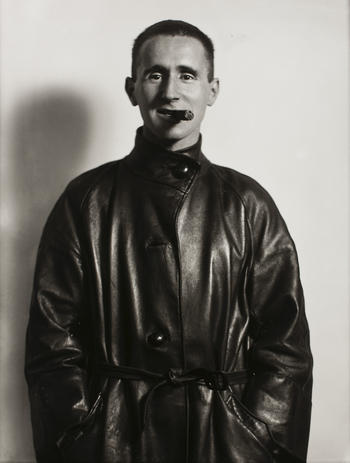

With leather coat and cigar – Bertolt Brecht decided how to present himself in the 1920s for a photo shoot at a studio in Augsburg.

Image Credit: bpk

Princeton, New Jersey, January 1938: Before the journalists arrive, Albert Einstein takes a moment to himself. Sixty at the time, Einstein knew what he owed his audience. With a few practiced motions, he fluffed out his gray-white mane until it stood out in all directions. Then he entered the library at the elite university, where the camera crews from the American weekly newsreels were already waiting for him.

With them was Thomas Mann. They made for a striking pair: Einstein, with his poorly fitting gray jacket and no socks, and Mann by his side in a black three-piece suit with a tie and handkerchief in his breast pocket. It was a real highlight for the media: a meeting between two German Nobel laureates who had fled to the United States to escape the Nazi regime.

Stefan Keppler-Tasaki has studied the two men’s appearance on camera so closely that he can describe and explain every single camera angle, every look, every movement. Keppler-Tasaki, a literary and media scholar, is a professor at the University of Tokyo. However, his research brings him back to Berlin time and again, and specifically to Freie Universität, where he was a junior professor from 2008 until 2012. An Einstein Visiting Fellowship from the Einstein Foundation is allowing him to build a working group at the Friedrich Schlegel Graduate School of Literary Studies, associated with longer stays in Dahlem.

He is just coming from the Deutsche Kinemathek archive, where he was watching old weekly newsreels. He is studying how prominent authors presented themselves on camera from the early 1920s until the 1950s. Keppler-Tasaki says that the main area in which scholars of literature have studied film thus far has been film adaptations of literary works, but that he is going one step beyond that: “The persona of the author, meaning the distinctive character they play in public, is also part of their work,” he explains.

When Thomas Mann went on camera, for example, he was portraying himself as Thomas Mann, in a sense. “He was his own work of art, the actor and director portraying himself,” said Keppler-Tasaki. Up until now, there has been a lack of categories for analyses like these: When did writers speak up in the new medium, how did they interact with the technical equipment, and what patterns of staging are there? Keppler-Tasaki aims to develop a poetics of writers’ appearances in film to tackle these questions.

Einstein and Mann Fight for a Shared Cause

How Thomas Mann planned his appearances as a writer is especially apparent in contrast to Einstein, the scientist, Keppler-Tasaki explains. Einstein presented himself as “electrified by his own genius,” while Mann was a respectable, hardworking artist with a bourgeois lifestyle. Mann’s cigar was a sign of his strong nerves, while his family offered support in the background.

Even with all the differences between them, Einstein and Mann complemented each other as representatives of the “true German culture,” and they had a common cause to fight for: securing the right to enter the United States for more Germans in exile. For the films made for the newsreel, situations were set up, emphasized, and simulated.

Even so, the writers were seldom happy with the recordings, Keppler-Tasaki says. Gerhart Hauptmann was shocked at how vain and pompous his “doppelgänger” on film seemed. Thomas Mann was annoyed at how hot the spotlights were, and by how close microphones were placed to his face – and that he had once forgotten to change clothes before filming, despite being well prepared otherwise. As a result, he was wearing a suit during the film, which was made in the afternoon, instead of tails, which would have been fitting for an event that was actually taking place in the evening.

It was a lapse that could never have happened to Bertolt Brecht. He had cultivated a proletarian look since moving to Berlin in the 1920s: leather jacket, cap, nickel-rimmed glasses. Not some cerebral writer, but a modern, big-city guerrilla fighter: That is how Keppler-Tasaki views Brecht’s persona. Brecht first perfected his image for still photos, but soon realized that film would be a much better way to capture the dynamic work going on in the “Brecht clique.”

Brecht bought an 8-mm camera of his own in 1928, even before he had become famous enough to appear in newsreels. He used it to document the historic moment when he, Kurt Weill, and Lotte Lenya created The Threepenny Opera himself on the spot. Keppler-Tasaki traces Brecht’s film “career” from these private films to recordings of his appearances before the McCarthy committee in the United States and all the way to his time in East Germany.

“Brecht worked as a director himself, so unlike Thomas Mann, he always knew where the cameras were and how he needed to act so that they would show him even if he wasn’t saying anything,” Keppler-Tasaki explains. During cultural events in East Germany, the other writers sat in a row, like chickens in a coop, while Brecht might do something like cross his arms and move backwards. Everyone who saw the event on film could see that he wanted to make the functionaries uncomfortable.

Just how strong his drive to hold power over his own image was became apparent upon his death 60 years ago, on August 14, 1956. He had refused to have any speeches during the funeral. It came as a bit of a shock to Keppler-Tasaki to see the film of Brecht’s burial, which was the fifth item in the newsreel, appearing, as he says, “after a report on tractor production and tips for hiking in the High Tatra mountains on vacation.”

Archival footage showing Brecht nodding mutely during events had been chosen. The text made the segment a political obituary of a kind the writer himself would never have wanted. These kinds of media tricks are difficult to interpret, Keppler-Tasaki says. On the one hand, the propaganda had the last word, presenting Brecht as an East German writer and party loyalist. On the other hand, the segment is so obviously contrived that the viewer notices what a hard time East Germany had with “capturing” its most famous author, as Keppler-Tasaki says. “Even in films like this governmentally approved weekly newsreel report, his overall attitude of resistance and opposition remains intact,” he explains.

This text originally appeared in German on September 24, 2016 in the Tagesspiegel newspaper supplement published by Freie Universität.